(All Russian pre-1918 Dates are given Old Style)

Introduction

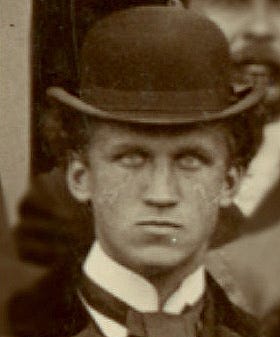

Throughout the year, the Imperial Theatres could be called upon to perform a royal duty. If that happened during the summer, appearances were in Peterhof, that magnificently laid-out palace complex, stretching all the way to the Finnish Gulf. One of the most high-profile gala performances there took place on 28 July 1897 when The Kaiser paid a state visit to Russia. The court was treated to Petipa’s ballet Thetis and Peleus. The event occasioned an ensemble photograph, shot in front of the Peterhof Theatre. For people into ballet history, many a face is recognisable and can lead to a spontaneous who’s who. Historian Andrew Foster shared a close-up of the character artist Alexei Bulgakov (1872-1954). What stands out are his eyes: steely blue-grey just got a new definition. What apotropaion was staring at us right out of 1897? Who was Alexei Bulgakov?

Early Years

Alexei Dmitrievich Bulgakov was born on 12 March 1872 as the son of a retired military servant. He entered the Imperial Theatre School on a Charles Didelot scholarship. One of Bulgakov’s later teachers was Marius Petipa himself. Petipa, the famous ballet master, gave up his second job two years before Bulgakov finished the school, and Alexei Dmitrievich graduated under the tutelage of premier danseur Pavel Gerdt.

‘… Bulgakov inherited from Petipa and Gerdt the noble and academic manners which shone through in the picturesque and restrained way he would express even the most passionate moments …’ said Soviet writer Vera Krasovskaya. The ambiguous compliment was a child of its time, as it rather depicts Petipa and Gerdt as old-order teachers who did not encourage a true-to-life delivery. Nevertheless, this foundation proved artistic enough for all times and ages Bulgakov was faced with. On completing his studies, Bulgakov starred in the graduation performance of 1889, Esmeralda, alongside his classmates Olga Preobrazhenskaya and Alexander Gorsky. All joined the Imperial Ballet on the customarily first day of June. Bulgakov’s dance roles were predominantly in operas. In ballet, he purportedly concentrated on mime. Bulgakov suffered from bronchitis, which presumably was a factor at play there. He started in the corps de ballet and among his early roles were a Merchant in The Talisman and the Moroccan Envoy in Zoraya.

Bulgakov’s first history-making role arrived soon after, that of the Ogre in Sleeping Beauty, with Dmitri Chernykov as his Ogre Wife. Petipa’s man-eater participates in the divertissement of Aurora’s wedding, being tricked by Hop O’ My Thumb and his brothers, whom he then gives chase. He wears a creepy mask and ditto costume, embellished with baby corpses in the manner of Indian warriors with scalps. Although Petipa condensed it into a playful rendition, Perrault’s original horror did permeate. Most Western producers omit Hop O’ My Thumb, presumed reason being the impracticality of bringing children to the stage - let alone seven boys. Following this, Petipa’s Ogres were barred from a worldwide break-through. Analogous, in a sense, was the ogres’ vanishing from popular culture, until they would make a spectacular comeback with the Oscar-winning Shrek by Dreamworks (the franchise commenced in 2001).

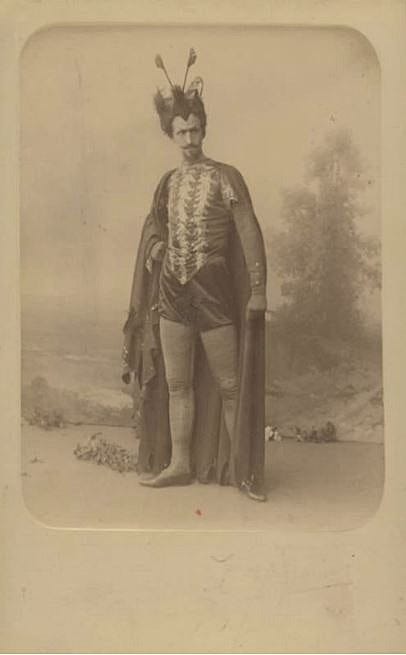

A year on, in 1891, Petipa created Kalkabrino. The ballet featured Gerdt as the titular smuggler, marking the beginning of his gradual transition into mime roles. The uncouth Kalkabrino lusts after the flower seller Marietta, and his wooing methods result in a church ban. Bulgakov’s character, evil-incarnate Malakoda, makes his entrance in Act II, arriving to reap the soul of the excommunicated Kalkabrino. The tall Bulgakov looked particularly impressive in his Mefistofeles costume. Amidst dances, led by She-Demons Vera Zhukova and Anna Johanson in fairies-gone-dark tarlatans, Malakoda changes a nameless spirit into Draginiatza, the spitting image of Marietta. This unholy, god-playing action links Kalkabrino to Swan Lake (1895) - the books were both by Modest Tchaikovsky (the composer’s brother). Draginiatza is conjured up to seduce Kalkabrino and drag him to hell. A depiction of Malakoda and Draginiatza survives via the theatre’s almanac, the imperial yearbook. The drawing suggests that the change happened on stage, with Bulgakov performing a cloak trick à la Nutcracker, Drosselmeyer helping Masha and the Nutcracker swap places with their adult alter egos.

Hopefully, the unpublished (and unfinished) autobiography of Modest Tchaikovsky contains more background, for there is but scarce attention allotted to Kalkabrino, and it usually centres around the mystery of Minkus’s score or Matilda Kschessinskaya’s debut. History easily overlooks Bulgakov’s casting: here the directorate broke with the habit of using established, elderly artists as villain, for Bulgakov was only 18 when he played Malakoda. Petipa must have watched keenly how the mimic ability and charisma of his former student developed, and how it could be put to use without scolding role-owners like Felix Kschessinsky (who acted Marietta’s father in Kalkabrino). Bulgakov appeared no less than 82 times in the 1890/91 season and was promoted to coryphee on a raise of 100 rubles. Malakoda had put him on the map, but Kalkabrino did not last, and his next big opportunity was some years off. Until then, Bulgakov had to make do with the Master of Ceremonies in l’ Ordre du Roi, an aide-de-camp in Le Roi Candaule, the Sculptor and a Gypsy in Paquita and the Burgomasters in Coppelia and The Harlem Tulip. He inherited the Augur in La Vestale from the retired Pyotr Leonov. Undoubtedly, the part required a mystical rendition, which suited Bulgakov well. He switched from Moroccan to Abyssinian Envoy when another corps-de-ballet member, Alexander Orlov, retired. It might have entailed a small promotion within Zoraya’s abundance of messengers.

A national tragedy occurred when Pyotr Tchaikovsky suddenly died (25 Oct 1893). The Mariinsky organised a memorial concert, which apparently could no sooner be given than on 17 February next, with an additional performance on the 22nd. The directorate decided to go for the next thing to a novelty: Swan Lake, Tchaikovsky’s 1877 ballet - perhaps surprisingly, new to the Mariinsky. The Swan Scene formed the ballet contribution to the evening. Apparently, the creatives had decided to let the Evil Genie for the moment materialise as ‘... some kind of predatory black bird with fiery eyes that hovers above the flock of swans ...’ (19 Feb 1894, Petersburgskii Listok). According to this description, the Evil Genie’s theatrical shape remained vague, and the yearbook does not mention an impersonated Evil Genie either. Since the Moscow stagings did use an actual artist (in 1877, Sergei Sokolov), the reason for this is unclear. Was Bulgakov intended but taken ill?

Before the full-length Swan Lake happened, Bulgakov played two new roles. The first was the minor part of Vulcan in The Awakening of Flora. The ballet was to outlive its purpose as pièce d’occasion for a royal wedding, that of the Grand Duchess Xenia to her first cousin (once removed) Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich. The Awakening of Flora premiered in Peterhof (25 Jul 1894), and afterwards transferred to the Mariinsky. Bulgakov received another raise.

Less than a half year later, on 20 October, Russia shook to its foundations when Alexander III was carried off by nephritis. He was 49 years old. The official theatres were obliged to observe a mourning period, so the Mariinsky closed its doors to the public. No performance was listed until January. Roland John Wiley noted that this gave the company ample time to prepare Swan Lake.

Bulgakov performed the second new part in Parisian Market, a week before Swan Lake to the nose. Veteran Timofei Stukolkin called it ‘Petipa’s little ballet,’ and remembered that the ballet master used to dance it with his first wife, Maria Surovschikova-Petipa, back in 1859. Now, the ballet had a one-off (8 Jan 1895), on the occasion of Maria Anderson’s farewell benefit. Anderson, the victim of a burning accident, danced Lisetta. The ballet may have been chosen because it was best suited to (re)design around her injuries. The one-act Parisian Market contained a scene buffo called ‘Le Jaloux Généreux,’ which Alexander Shiryaev remembers as ‘The Magnanimous Cuckold.’ The dancers, in the manner of the Commedia dell’Arte, were Stanislav Gillert as Pantalone, Vera Ivanova as La Checcina, Shiryaev as Brighella and Bulgakov as Scaramouche. Recalling Scaramouche, Shiryaev said that Bulgakov later became an excellent mime in villain roles.

Middle Mariinsky Years

Bulgakov’s largest contribution to dance history occurred on 15 January 1895, when the Swan Lake that was here to stay opened. He became the Evil Genie/Von Rothbart. The Evil Genie manipulates his captive swans and their queen to the very end, only to succumb himself in the act. Through the years, the Evil Genie evolved into a dance role, but the owl-like appearance of Evgeny Ponomarev’s design kept on inspiring future designers. Then there was his human guise for the second act. ‘Von Rothbart, as interpreted by Bulgakov, wears a fur-edged surcoat over armour, while on his cap is set a figure of an owl, like the crests borne on their helmets by knights at jousts or in battle,’ wrote Cyril Beaumont. Bulgakov’s knightly guise as Von Rothbart is also still echoed one way or another. He became the character’s exclusive performer at the Mariinsky but had to let go for at least one performance because of treatment.

The slightly younger Nicolai Soliannikov had to substitute for him with next to no rehearsal. Soliannikov imparts how he took some liberties, adjusting the eye make-up with the traditional, ‘wicked triangular eyebrows.’ Deductively, he applied a more naturalistic make-up than Bulgakov. The management showed itself tremendously pleased with Bulgakov’s work, as his salary was raised to 900 rubles while he received an extra 300 rubles for the treatment.

After a hiatus of a season, 1895/96 opened with The Nutcracker. The role of godfather Drosselmeyer, the plot-devising magician, was left vacated after Stukolkin had died (while performing Coppelius). Photos show a friendly, old, toothless Drosselmeyer. Nevertheless, the directorate took the opportunity to give the part to 23-year-old Bulgakov, passing by older mime/character artists such as Kschessinsky Sr., Gillert and Nicolai Aistov. One could say that Aistov was no favourite of Petipa, Gillert was better as good-natured fathers, leaving only Kschessinsky, who may have preferred to stick to Herr Silberhaus - insofar Drosselmeyer had been offered to him at all.

Drosselmeyer verifiably stands out as the most enigmatic role within Stukolkin’s gamma. A versatile artist if ever there was one, his repertoire did lean more towards the comical and tragic clowns. The counsellor/godfather should have become more mysterious - if not downright fearsome - in the hands of Bulgakov, whose make-up was all but comical. The line of sinister Drosselmeyers may have been born with Bulgakov. Bulgakov’s other debuts of that season, the Old Fakir in The Talisman and the Merchant in The Hump-backed Horse, were less enticing. Bulgakov took over Pyotr, the father-role in the Pugni ballet, from Stanislav Gillert on one occasion.

1896/97 brought Bulgakov the Vampire in Mlada and the Knight in Bluebeard. The grand ballet-féerie Bluebeard premiered 8 December, celebrating Petipa’s 50th anniversary in Russia. The small role of the Knight was created by Aistov, and Bulgakov performed it twice. The Knight disturbs a conversation between Bluebeard, Gerdt, and his young wife Ysaure, Pierina Legnani. He throws down the gauntlet on behalf of a vague master. It is safe to assume that the ominous Knight was a puppet of Bluebeard, beginning the set-up for Ysaure.

Did Bulgakov envy Gerdt doing Bluebeard? We cannot know how ‘rank-intimidated’ Bulgakov the man was, but most artists that get chances tend to want more. At the time of Kalkabrino, Bulgakov may have thought that a future in the first rank was unrealistic, but now he could, and he did not need a strongly positioned rival like Gerdt. Bluebeard was a role right up Bulgakov’s street. In turn, Gerdt would have watched his former student’s rapid development in a field he intended to branch out into. Bluebeard was revived by Legat for Gerdt’s benefit in 1910, and it was the last time he acted the part. By the time it was given its last show, in 1918, Bulgakov was no longer in Petrograd.1

No less than four state visits took place during that spring and summer. On 16 April, the Austrian Emperor travelled to Russia. Two acts of Sleeping Beauty were given in Franz Jozef’s honour at the Mariinsky, and Bulgakov played King Florestan’s servant. The other three visits were due in the summer and accordingly, three gala performances were listed. The first high guest at Peterhof was the King of Siam, Rama V, on 23 June. As crown prince Chulalongkorn, he was taught by the English Anna Leonowens and because of her story, his child persona lives on in film and musical. Russia was part of his Grand Tour, and some Romanovs and affiliated nobility were in attendance. Two acts from Coppelia were billed, with Bulgakov playing the Burgomaster.

A month later, Wilhelm II arrived. Now, all Romanovs and affiliated nobility were in attendance (…). The one-act Thetis and Peleus was presented; a reworking of The Adventures of Peleus (1877). Numerous characters from Roman mythology took to the stage, and the plot seemed drafted to enable the royal guests to point them all out. Bulgakov was Jupiter. With the lake as a real-life backdrop and clouds protruding from the wings, Bulgakov’s Upper God opened the ballet stately. He expelled the naughty Amor, Preobrazhenskaya, from Mount Olympus. Later, in the Apotheosis, Bulgakov towered above all the other gods, firmly holding on to his lightning bolt. The last gala performance was in honour of the French President, Felix Fauré. Bulgakov was not involved.

That autumn, audiences were treated to an extravaganza, Mikado’s Daughter (9 Nov 1897), with Bulgakov as Yuesugi-Sama, feudal lord and father to the ballet’s hero Ioritomo: Gerdt. Bulgakov was 25, Gerdt 53. Although Gerdt danced some of his jeune premier roles well into the 20th century, Ioritomo was his last new one. Mikado’s Daughter was also Ivanov’s last full-length ballet. Never again would the ballet world see Japonaiserie that maxed out. In the initial days of 1898, Petipa’s Raymonda premiered. Bulgakov interpreted the Senechal. His casting underlined the value placed on narrative, but any tall corps de ballet dancer, or a talented extra, could have done it. However, Bulgakov’s health may have been an issue, prompting the management to spare him an intensive rehearsal process.

That autumn, Petipa gave his last word on Pharaoh’s Daughter when he revived it for Kschessinskaya. Bulgakov missed out on the Pharaoh and The Nubian King, two roles he was cut out for, but Aistov (Pharaoh) and Kschessinsky Sr. (Nubian King) were two heavy-weights he can’t have expected to topple. He probably caught Petipa’s notorious commenting on Aistov in rehearsal: “... you are a lackey, not a pharaoh!”

Bulgakov was cast as the Black Slave, a character produced to … die. He is sacrificed when the Pharaoh sets an example of punishment for Taor, whom he suspects to know the whereabouts of his daughter. The Slave is brought in front of a large basket from which a cobra rears its hooded head. The High Priest incants, the snake bites, and the poor man dies writhing in agony. Bulgakov did all 13 performances in the ballet’s revival season and most shows after that.

The century’s final season had some top assignments in store for Bulgakov. On 21 November, Petipa brought Esmeralda back. It was Kschessinskaya’s turn to dance the role she craved since the beginning of her career. Aistov acted Claude Frollo in his own benefit performance, to be superseded by Kschessinsky Sr. thereafter. Bulgakov impersonated Clopin de Trouillefou, King of the Court of Miracles, the hideout for Parisian minorities and criminals. In January 1900, Prima Ballerina Assoluta Pierina Legnani had her benefit. Among the pieces she had requested to perform was the Ball Act from Cinderella, the ballet of her Mariinsky debut. Bulgakov portrayed The King, taking over from Aistov.

Then there was The Seasons, the second in a series of three fresh Petipa works. Neither the original nor the revivals made it, but thanks to Glazunov’s score the ballet’s beauty resonates down the years. Bulgakov was Winter in the opening section, wearing a bluish-green, frost-covered costume and beard. He directed four budding ballerinas metaphorically portraying his key features: Anna Pavlova was Hoarfrost, Julia Sedova Ice, Vera Trefilova Hail and Lubov Petipa Snow. The Seasons has the feel of a symphonic poem. Curiosity as to how Petipa treated it can never be satisfied, but the synopsis suggests that Bulgakov’s commanding presence was onstage from the beginning, invoking the storm, the music’s apt crescendo, with his staff and powerful port de bras. His salary was raised to 1200 rubles and he was promoted to the first rank.

Later Mariinsky Years

After the turn of the century, Bulgakov acquired more significant roles, gradually passing on smaller ones to younger colleagues. In 1900/01 he was Duke Mensky in Camargo and also did his first Coppelius. Bulgakov shared Coppelia’s eccentric doctor that season with Enrico Cecchètti, so prescribing audiences were in for a treat, enjoying two Coppelius’s who could not be more different. Maria, Petipa’s eldest daughter, had her benefit performance on 4 February. Among her chosen repertoire was Act II of Paquita. The complete ballet was beyond her technical abilities, but the benefit was her chance to have a shot at the Bolero, that act’s jewel in the crown. All she needed was two partners and she had but to ask role-owners Gerdt and Kschessinsky Sr., who are indeed credited in the annals. But did Maria ask them? The photos accompanying the benefit show a rejuvenated cast: the Lucien is the man Maria, as it were, found in her bed, Sergei Legat, and the Inigo Bulgakov. This was the single time Maria danced Paquita, so did Gerdt and Kschessinsky Sr. pull rank after seeing the photo shoot? The male cast Maria tried to launch did get to perform Paquita later on.

Fresh challenges followed with Don Pepino in Graziella and in Gerdt’s version of Javotte, Bulgakov shared the father-role, François, with Gillert. The domestic in Petipa’s sidestep, the pantomime Le Coeur de Marquise, was presumably a minor part. The piece is unique for Petipa’s collaboration with Léon Bakst.

A milestone in Bulgakov’s career followed when he performed the Grand Brahmin in La Bayadere, inheriting the role from Kschessinsky Sr. (21 Oct 1901). Fyodor Lopukhov referred to Bulgakov as the Brahmin of his time, either intending to compliment Bulgakov on his portrayal, or simply forgetting Soliannikov, who debuted a few years on.

Bulgakov’s Nikiya was Moscow’s Ekaterina Geltser. In her earliest professional years, Geltser had spent time in St Petersburg ‘to catch up on refinement’ in Christian Johanson’s class. She did some variations and ultimately covered for Legnani in Raymonda. Now she was allowed to sow what she had reaped before the capital’s audience. In Bayadere’s second scene, Bulgakov had, as Brahmin, an important dialogue with the Rajah Dugmanta, played by Aistov. The confrontation should have gained with these tall, stately artists. Literally, because personal motives notwithstanding, what we see amounts to a political discourse concerning a marriage of state, ideally as weighty as the duet between Philips and the Grand Inquisitor in Verdi’s Don Carlos - be it that in La Bayadere ‘the church’ is the asking party. At the end of the season, ‘Brahmin Bulgakov’ contributed again to dance history, so to speak, when he literally unveiled a rare talent in front of the temple: Anna Pavlova’s Nikiya.

Before Pavlova’s debut, there was another milestone for Bulgakov himself: his first title role, Don Quixote. The Mariinsky premiere took place on 20 January 1902. For his version, Gorsky had picked his former classmate to ‘do the Don,’ an age-old character. As Bulgakov was yet to turn 30, no doubt his gift as a silent actor was decisive. There Alexei Dmitrievich was, adoring Kschessinskaya’s Kitri, bullying Cecchètti’s Sancho, and startling his surroundings with autistic behaviour. Nevertheless, director Vladimir Teliakovsky thought that Bulgakov acted weakly. He noted this in relation to his acting in Griboedov’s play Woe from Wit, as Colonel Sergei Skalozub. The occasion was the exam performance of the imperial drama class. Two weeks earlier, Bulgakov was the house steward Melville in Schiller’s Mary Stuart. This indicates he prepared for a career switch.

Teliakovsky’s reservations aside, Bulgakov was rewarded with a gold medal for outstanding service, and his salary was raised to 1320 rubles. Don Quixote did not stay in Bulgakov’s hands exclusively, likely because of his activities in drama. In 1902/03, he was busy (studying) acting, and participated in plays with the Imperial Theatre School: Chekhov’s The Wedding and Uncle Vanya (as Mikhail Astrov) and Ostrovsky’s The Marriage of Belugin. Back then, Uncle Vanya was barely four years old. The last play mentioned in Teliakovsky’s diaries is The Golden Fleece by the Polish Stanislav Przybyszevsky, from 1901. The director remained generally critical of Bulgakov’s acting.

Ballet premieres passed him by: in December, the Italian Achille Coppini set La Source on the troupe, but the role of the Khan went to Gillert, and Bulgakov’s name does not feature on the cast list of Petipa’s Magic Mirror. Bulgakov did perform his old repertoire throughout the season, but in 1903/04, he did only two of the four scheduled Coppelias (one Coppelius went to Shiryaev and the other to Gerdt). There was, however, the Legat Brothers’ Fairy Doll, with Bulgakov as Bailiff. Bulgakov appeared just twice in 1904/05, as Don Peppino in Graziella. Aside from concentrating on acting, Bulgakov may have been indisposed, since one Graziella was done by Soliannikov. Someone whose health was surely deteriorating was veteran Kschessinsky Sr. After a stage accident with a trap door, Felix Ivanovich never regained his old strength. He died on 3 July.

Last Mariinsky Years

In the late summer of 1905, Bulgakov returned strongly. It appears he had abandoned his drama aspirations and was fully committed to dance once more, performing in 11 ballets. But there had been unrest in the country. After the tragic Bloody Sunday and the humiliating Russo-Japanese War, the need for reforms was voiced throughout the country. Fiercely. Violently. About half of the ballet company, Bulgakov included, kept quiet, but not so the progressive artists, who submitted a list with requests. The forerunners were Iosif Kschessinsky, Sergei Legat, Mikhail Fokine and Pavlova. Unavoidably, the group clashed with the management - the Tsar’s dancers asking for better work conditions was unprecedented. The company was gripped by a sinister atmosphere, even causing schisms within the artist families: Maria Petipa did not want changes, while her younger sisters, company members Nadezhda and Vera did. Romanov-tied Kschessinskaya opposed her brother Iosif, and Nicolai Legat rallied behind the conservatives, but his brother Sergei - Maria Petipa’s lover - sided with the rebels. When the inevitable counter-petition of the directorate came into play, Sergei was persuaded to sign, allegedly manipulated by Maria. Unable to live with himself, (an apparently hereditary) madness was triggered and he committed suicide.

A record of Bulgakov’s participation survives through Teliakovsky’s diary: ‘… during the tumult and grief following Sergei Legat’s memorial service [21 Oct], Bulgakov and Georgy Kyaksht tried to persuade the company manager, Georgy Vuich, to let the upcoming Sunday [evening] performance take place …’ (in the end, it was decided to cancel, P.K.).

Tempers kept getting frayed. Iosif Kschessinsky slapped his colleague Alexander Monakhov, and was dismissed with immediate effect. The cast sheet of his upcoming performance, a Paquita with Pavlova on November 27th, now listed Bulgakov as Inigo. Bulgakov was well aware he was replacing a beloved artist under the direst of circumstances. No imagination is needed to reckon that Pavlova needed to be pushed on stage with him, and the backstage protests, the orchestra bawling that ‘the shadow of death was invoked’ – Bulgakov caught it all.

Three days later, the strike was still a hot topic. Picture the rehearsal hall of the Theatre School, where Pavlova tried to convince Olga Chumakova that there was no strike on 16 October, possibly to insinuate that the management had cancelled her Giselle deliberately. When Chumakova told her not to lie, Fokine stood up for Pavlova and Bulgakov for Chumakova, a row ensued. Teliakovsky noted that the ranting went on for at least one and a half hours.

Bulgakov’s salary was raised to 2400 rubles in 1906 - the last raise he was to receive. He was back performing Coppelius and scheduled to do three of the four Bayadere performances, leaving one for Nicolai Soliannikov’s Grand Brahmin debut. Bulgakov played opposite Gillert, who had finally become The Rajah. Bulgakov also settled into playing Inigo.

An overdue debut occurred when Bulgakov got the Nubian King in Pharaoh’s Daughter. With his formidable stage presence, Bulgakov was not only ideal for the unabashed character, but with both father and son Kschessinsky gone, he was now the only artist with enough stature to tackle the role. While towering over Pavlova’s frail figure in a multi-coloured robe, he broadly gestured his intentions. As Aspiccia, Pavlova jumped, preferring a Nile plunge to harassment in a narrow cabin.

On 3 December, Kschessinskaya returned for 1906/07. ‘Her’ Esmeralda was on the programme again. Teliakovsky diarised on the evening, but doesn’t mention Bulgakov, a first-time Frollo - the second part he inherited from Kschessinsky Sr. It is plausible that he debuted in the role sooner, on 22 April, at a charity benefit for the mentally ill, organised by Kschessinskaya. The mentally ill were an ideal pretext for a stunt on her part: she let her dismissed brother make an unofficial appearance. She must have navigated blabbing colleagues, dressers and caretakers by bribing and cunning, all to get Iosif in without a backstage pass and to his Phoebus costume. The other principals, Bulgakov and Gillert, but also Legat (Gringoire) and Preobrazhenskaya (Fleur-de-Lys) must have been in on it. Naturally, Kschessinskaya was backed by her own Fafner and Fasolt, the Grand Dukes Sergei Mikhailovich and Andrei Vladimirovich. Both royal heavyweights were present in the auditorium, making Kschessinskaya’s action look official. Yet she did not stop there to cement her hedge, as she had also invited the family of Baron Fredericks, Minister of The Imperial Household - and confidante of the Tsar. Teliakovsky was not amused. Esmeralda sans père posed a switch for Kschessinskaya. Now she had Bulgakov manhandling her, shamelessly whispering ‘it is not too late, appartiens moi,’ in her ear when she was ready for the funeral pyre – or something else her father would have refrained from doing.

The 20th century let itself be known on the Mariinsky stage. ‘Angry young man’ Fokine had everything going for him, he was a principal dancer, gifted painter, teacher and choreographer - and in that field lay his ambitions. He was approached by Victor Dandré (Pavlova’s common-law husband) to arrange a performance for a charity evening, and so he came to do Eunice for the Society Against Child Cruelty. The libretto was based on Henryk Sienkiewicz’s novel Quo Vadis, playing out during the last days of Nero. The music was in ‘stereotyped ballet style,’ a serious flaw for Fokine, but a lack of time and funds had left him no choice but to browse the stock of unused scores. Eunice was choreographed in a non-balletic style, and one can wonder what a Ravel, a Tcherepnin, or, anachronistically, a Miklós Rózsa would have done with it.2 Kschessinskaya performed the slave girl Eunice, and Pavlova danced Acte. Bulgakov was Claudius, a sculptor. Conforming to Fokine’s new style, his mime should be more naturalistic, happily drawing on his experiences in drama. He was reviewed well by the notorious critic Valerian Svetlov.

The direct ancestor of Les Sylphides was on the same programme; the first version of Chopiniana. In the second of five short tableaux, the curtain rose on a nightly, Majorcan monastery. At the piano sat Chopin, impersonated by Bulgakov, made up to resemble him. The sick composer, plagued by hallucinations, is surrounded by ghostly monks. When they slowly close in on him, he is saved by his muse, Anna Urakova.3 Later on, some choreographers borrowed the motive, like Massine (Symphony Fantasque), Lavrovsky (Paganini) and Balanchine (Robert Schumann’s Davidsbündlertänze). At 11, Massine was the only one of them old enough to have seen this Chopiniana, but he didn’t mention it in his memoirs and chances are slim he did. But close on the timeline as these choreographers all were, they must have been ‘raised on’ and inspired by descriptions. Bronislava Nijinska was among those who praised Bulgakov’s interpretation of the composer, as was Fokine himself.

Eleven days later, Bulgakov ‘returned to the previous century’ with a performance of Petipa’s The Pupils of Dupré. Bulgakov and Gillert were cast as Gentlemen. The two mime artists appeared in ‘La Reverence Perdue’ and in ‘Jeux et Danse avec les Cadeaux.’

In 1907/08, Bulgakov applied for health treatment compensation again. This may have corresponded with an absence in the previous April, when he forewent a Nubian King and a Grand Brahmin. The management, in a changed course of action, refused this time.

Nicolai Legat’s The Little Scarlet Flower opened in December. After the failed Puss in Boots, it was his second full-length work, based on Sergei Aksakov’s fairy tale, to music by Foma (Thomas) Hartmann. The ballet master had trouble finding his voice as a choreographer, and The Little Scarlet Flower was widely criticised. There was a plethora of dances, strung together in a rather saliva-bound plot. Bulgakov was due in scene 3, as Monster in an exotic setting. In scene 6, Bulgakov transformed into a prince, danced by Fokine. Three days after Legat’s premiere, Stanislav Gillert passed away. Bulgakov had respected him. Nijinska wrote about her friendship with Bulgakov, and how they both lost someone they admired.4 Bulgakov now lost Don Quixote completely, and to add insult to injury, he was recast as Lorenzo, Kitri’s father. Bulgakov’s relationship with the theatre showed signs of wear, and Teliakovsky seemed to continuously scorn his Don.

Fokine’s ballets entered the regular repertoire during 1908/09. Three ballets situated in antiquity were on the playbill: Eunice and Egyptian Nights by Fokine, and Petipa’s Le Roi Candaule, revived without the master. Between the last performance of Le Roi Candaule (4 Feb) and the first of Eunice (12 Mar) lay a five-week time span, so artists who danced in all three ballets were in the unique position to compare the theatre’s antiquity old style (Petipa) to new style (Fokine). Pavlova was among them, with Diana in Le Roi Candaule, Veronika in Egyptian Nights and (now) the title role in Eunice, but Bulgakov too; besides repeating Claudius in Eunice he was The High Priest in Candaule and Marc Anthony in Egyptian Nights. Egyptian Nights was a premiere, given with Le Pavilion d’Armide and Chopiniana, by now the familiar version.

Amidst this, Bulgakov’s 20th year of service had arrived. Retirement was imminent and he applied for a farewell benefit. His request was declined, as all retiring artists should make 3600 rubles per annum to qualify for that. Bulgakov was a year too late, the decree had been effected per 1908. The rule conformed to the perverse reflex that money attracts money. Bulgakov did not let it rest. As an artist of the first rank, he asked for the title role in Le Roi Candaule to prove himself worthy of that sum. No doubt Bulgakov would have made an excellent Lydian monarch, but he was denied. Upping a salary for the sole reason to drag in a benefit was where the theatre drew the line. Then there was Gerdt, Candaule’s exclusive interpreter since 1891. Bluebeard, Abderakhman, Gamache and Candaule - Gerdt seemed bent on playing them until he could no longer open the lid of his sarcophagus, so to speak. When the frustrated Bulgakov was not seated to his liking for the Theatre School exam performance, he threatened to sue (Teliakovsky).5 Bulgakov’s final performance at the Mariinsky was on 15 April 1909, as Grand Brahmin to Pavlova’s Nikiya. Svetlov gave an appraisal of his colourful interpretation, grand gestures and expressive face.

The Ballets Russes and Moscow

It was probably disappointment with the Imperial Ballet rather than a taste for adventure alone that led Bulgakov to join Diaghilev. His newly formed company arrived in Paris on 3 May 1909. Rehearsals started the day after, in the Châtelet Theatre’s roof area. Because Bulgakov’s contract ended on 1 June, he was granted leave from the Mariinsky for the tour element leading up to that day. In the first programme, Bulgakov played The Marquis/King Hidraot in Le Pavillon d’Armide, sharing the stage with Moscow’s Vera Karalli and Mikhail Mordkin as Armida and René. Alexandre Benois later wrote that the double-role gained when Bulgakov performed it (as opposed to Soliannikov at the Mariinsky) and that he acted the transformation especially well. The premiere took place on 19 May, but the dress rehearsal on the 18th was already a gala performance in itself (Foster). The troupe caused a sensation - no news there. Foster asserts that Paris was ‘enchanted with everything Russian.’ There was much critical acclaim for Karsavina and Nijinsky, but according to Fokine, even more so for the young George Rosai, who performed Pavillon’s Jester Dance, the Bacchanal, with his wife Vera Fokina, and ... The Polovtsian Dances. The big dance piece from Borodin’s opera Prince Igor ignited a frenzy in the audience. Adolf Bolm was adulated as Chief Warrior. Undoubtedly, Bulgakov was happy for his young colleagues, but the feverish excitement, the raving reviews that kept rolling in only underlined his personal situation. Yes, after this French Xanadu he returned home with his colleagues in triumph. But for him it would be different: his Mariinsky backstage pass, still safely sitting in his pocket, would by then be an invalid piece of cardboard.

On the day Bulgakov’s contract with the Imperial Theatre ended, there was no performance. Did the dancers throw him a party, or at least drank with him to soften the blow? The next day, on 2 June, there was a full dress rehearsal for the second programme: Les Sylphides and Cléopâtre. Bulgakov played The High Priest in the Arensky ballet; a reworking of Egyptian Nights for which Fokine had cut the character Marc Anthony. Nijinska recalled how Bulgakov told her about the ‘first’ High Priest, Gillert, in Ivanov’s An Egyptian Night, intended for Peterhof. The ballet did not make it beyond the rehearsal stage. Since Bulgakov was cast in but two ballets, there was time to stroll along the banks of the Seine and contemplate. Back in St Petersburg, he submitted another request to the Minister of Court for a ‘monthly extra,’ citing ill-health, but he did not get beyond the half pension of 1140 rubles and the lump sum that had been allotted to him. The foiling here could be Teliakovsky’s, who sometimes disagreed with the ministry’s decisions, for the Minister of Court did green-light Bulgakov’s monthly increase of 150 rubles later on.

From 1909 to 1911, Bulgakov taught at the drama school of Alexei Suvorin, but in 1910 it was Paris again, for another summer season with Diaghilev. This time, the company was booked to perform at the Opera (Palais Garnier), and Bulgakov took part in two legendary premieres. The first was Scheherazade, in which he was Shah Sharyar. The Arabian harem fantasy had a libretto by Fokine and Bakst and was set to Rimsky-Korsakov’s symphonic poem of the same name. The ballet left an indelible impression on fashion and cultural life, pairing exoticism with eroticism. The story: no sooner than Sharyar and his brother Zehman go on a mock hunt, their women throw themselves into the arms of the male slaves, released by Cecchètti’s bribed Eunuch. Favourite Wife Zobeide (Ida Rubinstein) entertains herself with The Golden Slave (Vaclav Nijinsky) while the ensemble writhes in the background; indulging in quasi-erotic activity as well. The denouement was equally unprecedented and spectacular: at the height of the orgy, Shahryar’s men burst in and massacre all. Sharyar was the alpha male of the Paris repertoire. His moment comes when Zobeide pleads for her life. She is about to be pardoned, but then Zehman kicks the body of the Golden Slave, to prevent his brother from softening the verdict. In a flash, the eyes of Bulgakov’s Sharyar must have become as cold as ice again, but moments later, with the lifeless Zobeide at his feet, the curtain closed on a broken man. Benois wrote that Bulgakov was ‘a king from head to toe.’

Three weeks later, the second legend saw the stage: The Firebird. A variety of Russian folk characters inhabited an amalgam libretto, set to Stravinsky’s evocative score. One of these figures was the evil King Kostchei - Bulgakov. Along with the witch Baba Yaga, Kostchei belonged to the top baddies of Russian folklore. He already had an opera bearing his name, Rimsky’s Kostchei the Immortal (1902), and earlier a Moscow ballet by Julius Reisinger, simply named Kostchei (1873). The forgotten work had boasted many special effects by Karl Waltz. As Kostchei, Bulgakov is virtually unrecognisable in the photos, meaning he was tucked away in a make-up chair long before the curtain raised on Carnaval, or even while his colleagues were still enjoying their pre-warming up tea. Serge Grigoriev thought that Bulgakov was an effective Kostchei through his excellent mime and truly frightening looks.

Another major debut for Bulgakov was Hilarion in Giselle. At the Mariinsky, Gerdt held on to the role, which deprived other candidates of a chance and Diaghilev proved that Bulgakov was among them, if not first in line. His very expressive eyes should have worked their max to ward off evil when being danced to death by the wilis. In 1956, when Vladimir Levashev performed Hilarion at Covent Garden, his equally expressive eyes were captured to perfection in Paul Czinner’s film The Bolshoi Ballet (1957). Alexei Varlamov observed that Levashev continued the work of Bulgakov, who had been Levashev’s senior colleague from 1941 to 1954. Bulgakov’s remaining part for that Paris season was Pierrot in the charming Carnaval, a part originated by actor/director Vsevolod Meyerhold in St Petersburg.

Bulgakov saw the United States in 1911, when he toured with Gertrude Hoffmann’s company, playing Sharyar in her rip-off Scheherazade. Then Bulgakov and Gorsky got (professionally) reacquainted. Yuri Bakhrushin stated that the latter invited his old classmate to join Moscow’s Imperial Ballet. A new artistic life lay ahead. Bakhrushin wrote about Bulgakov’s ‘striking and expressive gestures, clean-cut yet not exaggerated,’ and on his ability ‘to subject all performance facets to create a masterly skilled and memorable picture.’ Bulgakov acted the ‘Moscow Monster’ too, in Gorsky’s Little Scarlet Flower. There were revised scenes and condensed acts, but the Golovin/Teliakovskaya designs from Legat’s production remained.

In the summer of 1912, Bulgakov performed Shahryar for the Ballets Russes again. Diaghilev evidently didn’t lose any sleep over his dalliance with Hoffmann , or forgave him. Bulgakov also joined Fyodor Kozlov’s UK tour, performing in his Scheherazade - another unauthorised one. The restless ‘Théodor Kosloff,’ a 1900 Moscow graduate, had been dancing at the Mariinsky, the Bolshoi and for Diaghilev. He was a talented young artist, and in Lopukhov’s words, ‘a phenomenal virtuoso.’

On 16 September, Bulgakov was back in Moscow. At last he danced Abderakhman in Raymonda, in Gorsky’s 1908 production. What Gorsky took from Petipa is hard to trace, but as the role was never ‘free’ for Bulgakov in St Petersburg, he should have relished the opportunity – despite wearing Korovin’s stuffy costume. Should the coat not have come off, it left little room for movement. Bulgakov was to reprise Abderakhman in the first post-revolution revival (1918). More debuts were Hans (Hilarion) in the Bolshoi Giselle, King Florestan in Sleeping Beauty and Gamilkar in Salammbo, Gorsky’s creation based on Flaubert’s novel.

1914 was the last year Bulgakov worked for Diaghilev. Aside from reprising Sharyar, there were two new roles for him: Potiphar in Joseph’s Legend (loosely based on the biblical story) and King Dodon in Le Coq d’Or. Fokine, reconciled with Diaghilev, choreographed both works. Joseph’s Legend’s music was by Richard Strauss. A somewhat unexpected breed in Diaghilev’s Russo-French stock, the Bavarian composer had met Diaghilev as early as 1897. The rich score, so reminiscent of his opera Salome, needed an enlargement of many instrument groups, and the violins were divided into three rather than two sections. Strauss’s librettists were Harry Count Kessler and his customary partner Hugo von Hofmannsthal. When Diaghilev proposed to relocate the story to Renaissance Venice, Joseph’s designers set their teeth in that readily. José Maria Sert took his call for the dramatic black-and-gold set from Veronese and Tintoretto, and Bakst created costumes that are among his most over-the-top beautiful. The splendid colours of the depraved court contrasted with the virginal white for Joseph. At the time of Joseph’s premiere, Moscow-graduate Leonide Massine was 18 years old, in typecasting as fit as Nijinsky for the naive, god-seeking ephebe: the difference between the sparsely-clothed shepherd boy and the high-crowned Potiphar could not be greater. It is a pity that there is no record of Bulgakov’s reaction when Bakst presented him with his super-high headpiece (on the right of Potiphar’s costume design a small cap can be seen, intended for the character’s nightly entrance). In his memoirs, Massine rather extols Bulgakov’s performance - on and off stage: ‘... Bulgakov, whose interpretation of the satiated, drink-sodden Potiphar was superb, proved a great help to me ...’

With Le Coq d’Or, Diaghilev went back to Russian storytelling. The satirical opera-ballet bore a close connection to Rimsky’s 1909 opera; Benois’s book was after Vladimir Belsky’s. Bulgakov was Dodon, Karsavina the Queen of Shemakhan and Cecchètti the Astrologer. There was a range of emotions for Bulgakov to emit: Dodon’s cold-heartedness, shown when he doesn’t really mourn his dead sons, his fierce temper, shown when he kills the Astrologer, but above all laziness. His sorry existence is ended by the titular Golden Cockerel - a dive by a prop. In a photo for the Comoedia Illustré, Bulgakov is seen sitting on his throne with a self-content expression. Massine thought that ‘he gave an impressive performance,’ and Grigoriev was particularly delighted with the scenes between Karsavina and Bulgakov, which were ‘an ingenious mixture of dancing and mime.’

War and Revolution

From 1913 to 1917, Bulgakov functioned as first régisseur for Moscow’s Imperial Ballet, a job compatible with performing, similar to Aistov and Sergeyev in St Petersburg. Teliakovsky diarised hiccups. An example concerns a rather theatrical scene, wherein Count Vladimir Rostropshin let it be imparted to Mordkin that he did not partner Alexandra Balashova well. Rostropshin, although assistant to the director, clearly acted here from his elevated social position. Bulgakov clumsily delivered the message to Mordkin during a performance. Naturally, the star did not take it kindly. Later, in 1915, Balashova and Mordkin complained to Teliakovsky about Geltser. By that time the aging prima donna’s ego had well outgrown the Bolshoi building, she tried to control the company by meddling with casting (including benefit performances), forbidding Balashova to choose her own divertissement numbers, making scenes and picking fights. Teliakovsky intended to put a stop to it and reproached Bulgakov for not dealing with it. Then again, even if it was in the job description, you might ask of a régisseur to stand up alone to the likes of not just Geltser, but also principal dancer Vasily Tikhomirov, conductor Andrei Arends and Gorsky, all of whom ate out of the ballerina’s hand.

In the midst of the WWI (20 Feb 1916), Teliakovsky made a serious entry on the subject. One of the managers, Sergei Obukhov, reported to him how dancers and administration alike had issues with Bulgakov and recommended to relieve him of his (régisseur) duties. Bulgakov, clearly ignorant of it all, asked Teliakovsky if the company had plans for his 25th anniversary (having deducted the post-Mariinsky two-year hiatus). The director broke it to him that no one had planned anything of the kind, because everybody was deeply unhappy with his performance. Two months on, a dismissal was apparently off. Teliakovsky recorded a meeting with Bulgakov and Obukhov on the theatre’s war-related problems such as the depletion of artists, partly because young male artists were called to war, and the dwindling resources.

The 1917 revolution caused many dancers to flee Russia. Bulgakov stayed. Did he surmise that he would lose out when competing with great names for teaching jobs and that his specialism, mime, was not in demand enough to make a living? That, or neither Western Europe nor the US were enough of a lure in themselves for Bulgakov after having experienced both.

A highlight in Bulgakov’s career was to follow a year on, Stenka Razin. At 46, he created his second title role, the first one made to suit his talent. Where Don Quixote had been a case of filling in required space, the Ukrainian hetman Razin was far less pre-described, since an earlier version by Fokine had failed to set a standard. Elizabeth Souritz attested that there is little to go on Gorsky’s Stenka Razin in the theatre archives and that accounts are lacking. Yet she managed to paint a clear picture - both denotative and connotative - of the ballet. Souritz claimed that the work ‘marked a fresh phase in Gorsky’s creative life’ (which has the aura of a politically inclined one, born out necessity, P.K.), and that it was the first to cater to a revolutionary people. Not well known in the West, and more appealing to Muscovite audiences than to Petrograd ones (Souritz), Razin was a 17th-century Cossack who stood up against the Tsarist regime. In 1918, celebrations were in order: the Bolsheviks had pulled Russia out of the war, and the first anniversary of the revolution had arrived - hardly surprising that Razin was welcomed as a Soviet hero avant-la-lettre.

The story in a nutshell: surrounded by the enemy, Razin sacrifices his beloved captive Persian Princess by ‘entrusting her to Mother Volga.’ This ‘heroic feat’ is acclaimed by his men, now better motivated to fight the Tsar’s troops. Critics opined that ‘... the revolutionary theme was treated with the help of conventional forms of the old ballet ...’ Nevertheless, raw folklore steps were used instead of stylised character dance for the central corps de ballet - Stenka Razin preceded heroic male dance in Soviet ballet (Souritz). Bulgakov - biased or not - thought the mass scenes to be ‘impressive’ (Roslavleva). Despite mixed reviews, Gorsky held on to his creation and programmed it for the New Theatre in 1922.

Then Bulgakov interpreted his second Drosselmeyer, in Gorsky’s Nutcracker. Among the numerous changes was the first time Clara and the ballerina morphed into one character, re-forging the ballet as a growing-up metaphor. This ensured The Sugar Plum Fairy’s move westwards, as it were. The influential version premiered on 21 May 1919. Pre-production had begun as early as 1912, but then war, revolution and less profound reasons caused the hefty delay. Souritz reported that ‘participants in the ballet saw how Bulgakov added a particular elegance to Drosselmeyer that set him off from those around him,’ and that Gorsky’s character was devoid of mystique and more of a kind grandfather, unlike Ivanov’s. The idea of Drosselmeyer’s hiding in the clock was retained.

On 27 February 1920, Bulgakov played the Evil Genie/Von Rothbart in Gorsky’s last and most controversial Swan Lake, created together with theatre-maker Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko. Think here of the preserved Odette and Odile costumes by Vasily Dyachkov: the characters appear as flashy silent movie divas with (removable) Sirin and Alkonost wings. Souritz described how the period leading up to the premiere was probably the most difficult to date. Inflation ran high, typhus raged, rehearsals had been beset by extreme cold (dancers were forced to wear fur coats and hats) and the theatre was divided by factions. Gorsky complained he was thwarted by the conservatives. Balashova and Geltser did not take part. The Prince, Viktor Smoltsov, claimed to be ‘devoid of feeling’ when dancing with Elena Ilyuchenko,6 the young and untried Odette. Smoltsov was replaced by Leonid Zhukov. Bulgakov tried to quit the production too but the directorate forbade it. Did he feel the need to protect his role? To keep the Ivanov/Petipa conception from overt artifice? Contemporary critics opined that Gorsky’s pre-revolutionary versions ‘seem to have kept too much of the old’ (Souritz). If that pertained to Gorsky’s earlier treatment of the Evil Genie/Von Rothbart as well, it explained why Bulgakov acted up only in 1920 (the driving force behind the ‘de-balletising’ was Nemirovich-Danchenko). History perceives Bulgakov as a supporter of traditions in ballet. His behaviour during the 1920 Swan Lake contributed to that idea, or even originated it. But what if role integrity was just bycatch? Was Bulgakov in trying to detach himself from Swan Lake being opportunistic? The ever-present spots of quicksand in any theatre can widen at any time, and they surely did so back then at the Bolshoi. Bulgakov witnessed first-hand how Gorsky, his poor peer, lost ground and started to go downhill. With betting on other factions, Bulgakov could be called a realist.

After the Civil War and Gorsky’s demise, Bulgakov worked with Zhukov in his version of Scheherazade, and with Tikhomirov. Tikhomirov was a Bolshoi stalwart, educated in Moscow and then in St Petersburg by Gerdt, Shiryaev and Platon Karsavin. He had often opposed Gorsky’s experiments and radicalism, and now he occupied himself with bringing things ‘back to normal.’

For the 100th anniversary of the Bolshoi Theatre, Tikhomirov staged the second act of Schneitzhoeffer’s La Sylphide. Former soloist Serafima Kholfina, a student at the time, recalled the excitement about the jubilee, and how Tikhomirov came to the school to select pupils. Tikhomirov himself, 49, danced James, and Bulgakov played Madge to Geltser’s unlikely Sylph. The ballerina had always been a terre-à-terre dancer, while her age, equal to that of her partner, didn’t quite redeem the lack of airiness. Bulgakov, for the first time en travestie, was delightfully free from these problems. The evil Madge is a dream for any character artist, and Bulgakov, with his icy stare and seasoned mime talent, should have delivered his audiences a good fright. Thanks to Kholfina, a detailed description of Bulgakov’s Madge survives: ‘... Bulgakov, tall, broad-shouldered, his grey hair tousled, wore a tunic in a brighter colour than the other witches. He stood on a dais at the kettle, conducting all that happened on stage with broad gestures […] with typical acting skills, Bulgakov showed how the poisoned scarf would be placed around the Sylph’s shoulders. [His] Madge threw the scarf up so that it spread in the air, [and then] the gauze cloth descended flowingly back into her arms. The witch cackled with her toothless mouth (Bulgakov did this so well) and handed the scarf to James. Tikhomirov, James, thanked her happily and left to find the Sylph. Once on her own, Madge laughed menacingly ...’ Kholfina also described the curtain calls: ‘... The success was unprecedented. A sea of flowers. Baskets, bouquets and more baskets. Most of the acclaim concerned the Sylph. The curtain rose time and again and the audience kept yelling “Gelt-ser! Gelt-ser!” I stood on stage with the other dancers and saw Ekaterina Vasilievna’s tired face. She took her calls with her hands placed on her heart. Tikhomirov and Bulgakov stood beside her, modestly bowing their heads ...’

Going by Kholfina, you would believe Taglioni’s reincarnation had arrived. According to Sergey Belenky, claques were a thing of the past, but the behaviour of Geltser’s followers was not inferior to that of a paid audience. In 1926, Tikhomirov turned his back on Gorsky’s Gudula’s Daughter and brought Esmeralda back; Vasily Dmitrievich remembered and valued the last Mariinsky revival. Bulgakov became Claude Frollo once more, this time to Geltser’s ‘Daughter of the People’ - the Romantic ballet’s new subtitle, conforming it to the artistic program of 1920s Russia. Another ‘conformity’ was found in the Prologue, which opened on an empty stage - safe for Bulgakov. His commanding figure stood in one of Notre Dame’s towers. ‘... That stone, medieval mass with chimeras at the top, a motionless canon. According to the director’s plan, it represented the power, strength and oppression [that] the poor people from Paris suffered ...’ (Kholfina). In the same year, Bulgakov embarked on a three-year stint of teaching at the Moscow Choreographic School.

Final Years

A landmark ballet was Reinhold Glière’s The Red Poppy. Lev Laschilin and Tikhomirov produced the first version in 1927. Souritz asserted that it was the creatives’ answer to a ten-year struggle about what to do with classical ballet. Hiding behind a contemporary theme though, was a return of ‘stereotyped divertissements’ - running counter to the Leningrad attempts of Lopukhov and the avant-gardist Kasyan Goleizovsky, with whom Bulgakov, incidentally, never worked. The Red Poppy firmly dominated the performance list during its initial run. It was set in a contemporary China, where Geltser’s dancer Tao-Hoa meets a handsome Soviet Captain, Bulgakov. The noble Captain stands up for the abused coolies and becomes the love object of Tao-Hoa. She presents him with a red poppy. Eveline Chao reports on how the story became subject to international controversy later. High-up members of the Chinese community warned Mao Zedong not to go see the ballet when he visited Moscow in 1950 (he went to see Swan Lake instead). Considered problematic were the view on the Chinese Revolution and the Communist Party, the poppy flower as a reminder of the humiliating Opium Wars, plus the fact that Tao-Hoa was a dancer – it meant that the Chinese top thought they were being served up a prostitute. Conflict centred less around Bulgakov’s character. The Captain was the ballet’s non-dancing Soviet hero. It masked another old-way custom: an elderly dancer performing the male lead. But now there was no Gorsky or Legat to spring up from the sailor ranks and perform a variation in Gerdt’s stead. The Captain also has the feel of a correction on Madama Butterfly’s Lieutenant Pinkerton, an American. Playing out in Japan, the actions of this anti-hero lead to the hara-kiri of Butterfly, Cio-Cio-San. Bulgakov’s nameless Soviet Captain did not raise a native girl’s hopes, did not marry her - and didn’t knock her up.

In 1934, Bulgakov portrayed the Duke in Giselle. The revival was set by his ex-colleague from Leningrad, Alexander Monakhov - once slapped by Iosif Kschessinsky. The Duke was now Albrecht’s father and restyled as ‘Sovereign Prince.’ The aging Bulgakov also created Proserpo in Three Fat Men (1935), by Alexander Radunsky. He went back to the King in Lavrovsky’s post-war Raymonda (1945) and played both the Marquis de Beauregard and Louis XVI in The Flames of Paris (1947). Lavrovsky’s Romeo and Juliet was brought to Moscow in the winter of 1946. Friar Laurence became Bulgakov’s last new part. There, in front of him, waiting to be blessed, kneeled the daughter and niece of his one-time colleagues, Sergei and Pyotr Ulanov and Maria Romanova: Galina Ulanova, leading ballerina of the Soviets. Bulgakov’s Laurence married her and provided her with poison. ‘... He played unusually touching, with a wisdom and longing to reconcile that what could not be reconciled ...’ (Maria Gorshkova).

Bulgakov was on stage at least until April 1950, when he, aged 78, performed The Duke in Lavrovsky’s Giselle with Ulanova in the title role and Maya Plisetskaya as Myrthe, and Louis XVI in The Flames of Paris. Ilyuchenko, once his Odette, was now his Marie Antoinette. Bulgakov also occupied himself with regisseur tasks again and worked with dancers such as Alexei Ermolaev. Alexei Dmitrievich Bulgakov made Honoured Artist of the USSR in 1949, in his case something of a lifetime achievement award.

Lopukhov’s following comment captures Bulgakov’s legacy tellingly: ‘… Bulgakov has the ability to imbue the conventional balletic gesture with realistic expressiveness … ‘ It sounds like the key to any credible performance involving ballet mime and contradicts Krasovskaya’s earlier quoted remark (that Bulgakov was passed on Petipa and Gerdt’s noble and academic manners, which he applied to even the most passionate moments). More generally, the writer accorded how ‘Bulgakov lived through many different epochs of Russian ballet.’ To widen this perspective: Bulgakov was of that fascinating generation born in the days with a Tsar, a rigid class system, horse-drawn carriages and no electricity. He would depart from a world without a Tsar, a not-so-classy rigid system, planes and televisions - a world that prepared for space flight, forever changed by revolutions and two wars, akin to his surviving peer Nicolai Soliannikov in Leningrad. Were the two men in contact? Did they dare compare? For they had been fortunate enough to be ‘raised by’ and working with Petipa. Despite having been around other talented people, none of them had commanded enough artistic authority to fill the void left by him.

Alexei Dmitrievich Bulgakov died on 14 January 1954. He rests at Moscow’s famous Novodevichu Cemetery. Bulgakov shared the stage with ballerinas from Carlotta Brianza and Pierina Legnani right up to Maya Plisetskaya. He was their antagonist, keeper, conjurer and worst nightmare - and in doing so he taught the ballet world how to do bad.

© Peter Koppers

Notes

1) Ivan Kusov took over Bluebeard for a one-off in 1918, his benefit performance.

2) Rózsa’s film score for MGM’s Quo Vadis of 1952 so evokes the atmosphere of antiquity.

3) Urakova was the original Bonne Fée from Harlequinade, and Fokine observed that Urakova specialised in good fairies.

4) Gillert, Nijinska’s fellow Pole, had played a pivotal role in getting the Nijinsky children placed in the Theatre School. It understandably earned him Bronislava’s eternal gratefulness.

5) Failing to acquire mezzanine for the same event, Pavlova, a vulgar cookie when she chose to be, wrote an abrasive letter.

6) Elena Ilyuchenko acted Lady Capulet in Lev Arnshtam’s Romeo and Juliet, a film with Galina Ulanova (1955).

Sources & Bibliography

Sergey Belenky

Andrew Foster

Sergey Konaev

Grigory Tchicherine

Artistic Heritage of Karl Waltz in the Context of the Development of the Decorative Arts of the Opera&Ballet Theatre in the Last Third of the 19th Century (Tvortchestkoje Nasledii K F Waltz v Kontexte Razvidija Dekoriatzionnova Isskustva Bolshevo Teatra Poslednii Tretii XIX Veka), Dmitri Rodionov

Bolshoi Archive

Dancing in Petersburg, Matilda Kschessinska (translated by Arnold Haskell)

Diaries, Vladimir Teliakovsky

Early Memoirs, Bronislava Nijinska

Era of the Russian Ballet, Natalia Roslavleva

Fund Guide on Manuscripts and Documents (Putevoditel’ po fondu “Rukapi i Dokumentii), St Petersburg Theatre Museum, T Vlasova, etc.

Josephslegende, Harry Graf Kessler and Hugo von Hoffmansthal

Josephslegende, Mervyn Cooke (2013)

Componist F A Hartmann - in Employ of N G Legat (Kompositor F. A. Gartmann - Sotrudnik N. G. Legata), Krimskaya

Leader of the Russian Ballet, Nicolai Soliannikov*

Léon Bakst, Charles Spencer

Materials for the History of Russian Ballet vol. II, Mikhail Borisoglebsky

Memoirs of a Ballet Master, Mikhail Fokine

Mikhail Fokine, N Teofanov etc.

My Life in Ballet, Leonide Massine

Nutcracker programme - Vladimir Levashev (‘Schshelkunchik,’ posviachennomu V. A. Levaschovu), Alexei Varlamov (1971)

Remembering the Masters of the Moscow Ballet (Vspominaja Masterov Moskovskava Baleta), Serafima Kholfina

Reminiscences of the Russian Ballet, Alexandre Benois

Russian Ballet Theatre at the Beginning of the 20th Century (Russkii Baletnyi Teatre Nachala XX Veka), Vera Krasovskaya

Sixty Years in Ballet (Shest’desyat let v balete), Fyodor Lopukhov

Soviet Choreographers in the 1920s, Elizabeth Souritz

The Ballet Called Swan Lake, Cyril Beaumont

The Ballet that caused an international row (2017), Eveline Chao, BBC Culture

The Diaghilev Ballet, Serge Grigoriev

The History of Russian Ballet (Istoriya Russkovo Baleta), Yuri Bakhrushin

The Legat Saga, John Gregory

The Life and Ballets of Lev Ivanov, Roland John Wiley

The Petersburg Ballet, Alexander Shiryaev

The State Theatre Library Museum of St Petersburg

* from Marius Petipa, Meister des klassischen Ballets, Eberhard Rebling, Petipa Materials

Photo Credits

A.A. Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum, Artchive, Bolshoi Archive, St Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music / Санкт-Петербургского государственного музея театрального и музыкального искусства, St Petersburg State Theatre Library / Санкт-Петербургская государственная театральная библиотека, Mariinsky Theatre Archive, Collection of Peter Koppers, Salvador Sasot Sellart