(All Russian pre-1918 Dates are given Old Style)

Introduction

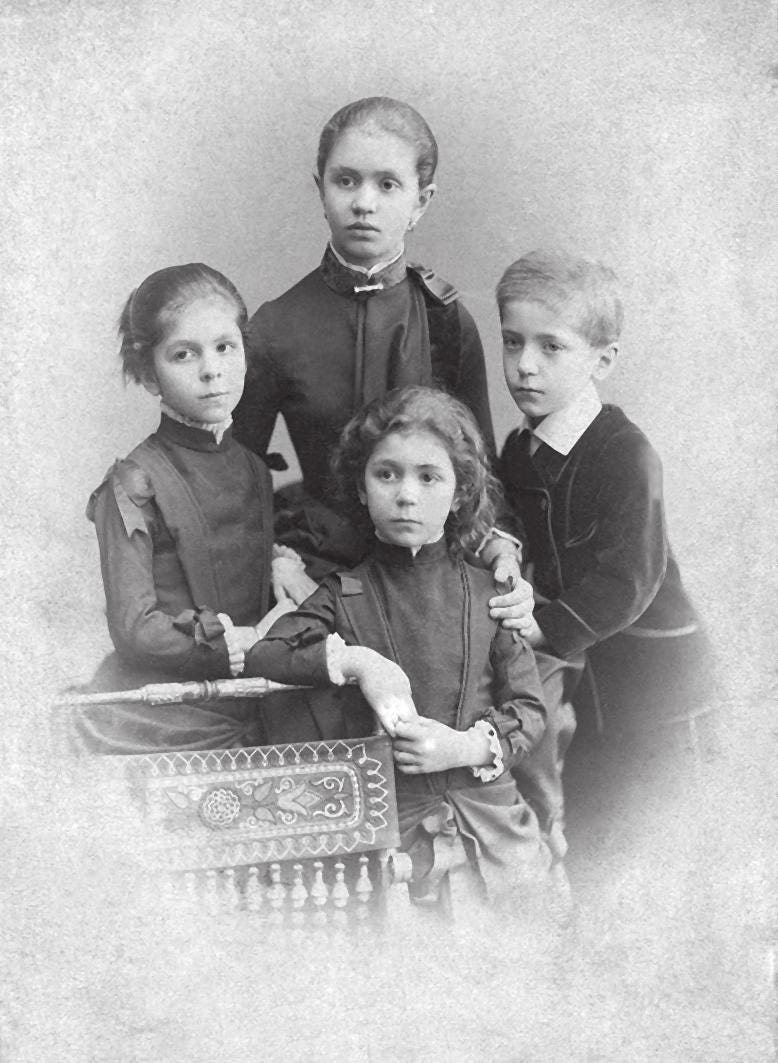

There are at least two known photographs of The Magic Fairy Tale, a choreographic ditty Marius Petipa created for the Imperial Theatre School. The piece, about a dwarf king, a fairy and a shepherdess, premiered in the school theatre on 10 February 1892. The said photographs, depicting the youngest pupils (one class below making the cast list), are all what is left of it. In the centre sit two small girls, holding a wicker birdcage. At left is Anna Pavlova, at right sits the girl often identified as her classmate Lubov Petipa, the ballet master’s fourth daughter. In one photo Pavlova looks shy, and Petipa stares rather dreamily into the camera. Did the photographer then encourage the girls to say cheese, playing to their vanity by pointing out their importance, singled out to carry the prop? If he did, the other photograph was taken afterwards, for now Pavlova treats the camera to a smile. It is clear Lubov also responded, as she has raised her chin somewhat - however, her dreamy stare remains detached, nonchalant. Did she really want to be there? Of course, should photos with a radiantly smiling cage-holding Lubov be produced this little theory can be declared null and void, but indeed, such a photo has yet to surface. Who was Lubov Petipa? Like so many children of famous people, her name sits in the far corners of history, only lighting up unintentionally when someone looks for info on the parent.

Childhood and Theatre School

Lubov Mariusovna Petipa was the fourth child of the Frenchman Marius Petipa (1818-1910) and Lubov Stakilevich (better known as Savitskaya, 1854-1919). The dancer Petipa, himself a dancer’s son and brother, had come to St Petersburg in 1847. He entered the Imperial Theatre as Premier Danseur, and proceeded to create great works in the capacity of 2nd and then 1st Ballet Master. In so doing, he gave Russia’s capital the leading position in the dance world. The dancer Lubov Leonidovna was Petipa’s second wife. Together, they had six children. Their two boys, Victor and Mari, were to become actors, while all four girls, Nadezhda, Evgenia, Lubov and Vera, studied dance. Except for Evgenia, who sadly died aged 15, all girls made it to the profession. Petipa’s eldest daughter, Maria, from his marriage to the ballerina Maria Surovshchikova, became an imperial dancer as well. She ended up being a celebrity, a tabloid-press favourite, famed for her beauty. In the theatre, hers was a special niche which mainly consisted of (what came to be called) character roles, in common with her far less spotlighted half-sister Nadezhda.

Much information on the Petipa family life comes to us through Vera, the youngest child. In her all too brief memoirs, Our Family, written in her later years, she describes a loving but rather boisterous household. She fondly remembers her sister Lubov, Luba, as ‘a rare soul.’

Vera also imparts how Petipa cherished and nourished the talent of the lamented Evgenia. By all accounts, she was a true ballerina in the making. After she died from cancer in 1892, Petipa had the ballet studio, in use to teach his daughters, removed from their home. His attention now turned to Lubov. From then on, she boarded the Theatre School. Ballerina/teacher Ekaterina Vazem reckoned Lubov had the potential to be a soloist and perhaps a ballerina - like her unfortunate sister.

By the end of the 1890s, Lubov’s training at the Theatre School neared completion. After studying with Vazem, she found herself in Pavel Gerdt’s class for the last phase of her education, as did Anna Pavlova. Their careers would more or less keep pace. The renowned Premier Danseur is sometimes credited with teaching Pavlova how to do a soaring leap. If that is so, the same applied to Lubov - both were noted for their jump. Around the same time, Lubov started to participate in the theatre officially, sampling the professional stage as court lady in the 1898 premiere of Raymonda, and so experience her father choreographing for the company first-hand. Lubov was chosen for the ‘Jeux et Danses,’ as were her classmates Stanislava Belinskaya, Nutcracker’s first Clara back in 1892, and Larisa Andrianova. Together with some boys of their year, they were mixed with the graduating Julia Sedova, Lubov Egorova, Mikhail Fokine and Mikhail Obukhov. In order to showcase the graduates and senior students of 1898, Petipa chose an older work of his, the Anacreontic The Two Stars. The main parts, the titular Stars, were given to Belinskaya and Pavlova. Lubov danced the thirdly billed part; Venus. The role cannot have been the worst deal, for as Venus, Lubov should have danced with Adonis, a mortal very much connected to the goddess of love, impersonated by Fokine. In October of that year, the ballet Pharaoh’s Daughter, Petipa’s break, enjoyed a major revival. It was the benefit performance of Anna Johanson, who herself participated as Ramze, the favourite slave. Lubov was cast for the Almées, a pas de trois from the Grand Ballabile des Caryatides Animées, together with Belinskaya and Pavlova.

In the midst of 1898/99, Lubov was legitimised (her parents had not been married at the time of her birth), and at the end she enjoyed her graduation performance (11 Apr). She appeared in the Mikhailovsky Theatre. The programme consisted of three ballets: Clorinda, by Alexander Gorsky, The Dream of Fidi, by Enrico Cecchètti, and The Imaginary Dryads by Gerdt. The inquisitive balletomanes were eyeing the ‘experimental’ ballet on the bill, in which Lubov was selected for the title role: Clorinda, Queen of the Mountain Fairies. The ‘experiment’ didn’t pertain to the subject, which was commonplace, but to the modus operandi. It was based on a recently developed system for dance notation. Clorinda’s creator, the dancer Alexander Gorsky, had taken up responsibility for it after the inventor, his colleague Vladimir Stepanov, had suddenly died.

Clorinda had a sizeable cast that included the future stars Tamara Karsavina, Lydia Kyaksht, Elsa Vill and Samuil Andrianov. Young Vera Petipa frolicked in the Polka Capricieuse. Fyodor Lopukhov, cast in the Danse des Enfants, explained the excitement later, recalling that in order to test the system’s possibilities, Gorsky had created Clorinda on paper rather than in the studio. The (older) students, Lubov included, learned their parts by themselves from personalised, written instructions. This way Gorsky was free to concentrate on artistic matters while setting the work; busy with ‘how,’ not ‘what.’ So as opposed to using notation for revivals, it was a tool to create for Clorinda. Gorsky did not continue the experiment, but he did set Clorinda on the Moscow company two years later, where Evgenia Shishko danced the Mountain Queen.

Clorinda’s score was produced by Ernest Keller, a flautist in the Imperial Orchestra, and the libretto was loosely based on Hans Christian Andersen’s Snow Queen. The dark story surely balanced Gerdt’s light-hearted Imaginary Dryads, which was last on the programme. In a rather modern set-up, Clorinda’s single act was divided into scenes named after the times of the day. It ran as follows: the eerie queen Clorinda is seen bewitching a Tyrolean peasant, Franz, danced by Ivan Ivanov, who has climbed her mountain to find an eagle feather for his mortal beloved, Ida - Elena Makarova-Yuneva. With a disregard for human-life value often witnessed in supernatural creatures, Clorinda hurls her love interest from a cliff after seducing him. When Ida mourns Franz, the mountain spirits conjure up a snowstorm to finish the girl.

Clorinda was quite intense to carry for students, especially for the title role’s interpreter, to whom it all came down. The inhuman nature and vampish qualities Gorsky endowed the Mountain Queen with were designed with Lubov’s apparent acting gift in mind.

In producing a female being, potentially fatal to man, Gorsky had Lubov and her peers sample a preferred ballet theme, used in works such as Giselle, The Daughter of Snows and Nenuphar. On the brink of the 20th century, Clorinda predated rawer interpretations like Fokine’s Egyptian Nights and Thamar. Robbins’s The Cage, Petit’s Le Jeune Homme et la Mort and Le Rendez-Vous and Balanchine’s Prodigal Son were to follow later - although the Siren is not after the son’s life, just after his belongings. Clorinda’s seduction scene, culminating in Franz’s demise, is part of the notations found in Two Essays on Stepanov Dance Notation, a publication by Gorsky. There is a direct line between Clorinda and Giselle’s Myrthe that uniquely pertained to Lubov. Her cold Mountain Queen should have given a satisfied Petipa the idea - or the assurance - she was ready for the Queen of the Wilis, that ultimate example of a spirit that had lost her humanity. Lubov was to take on the famed role in a few months.

After The Dream of Fidi, which mainly involved Cecchètti’s students, Gerdt concluded the evening with his version of The Imaginary Dryads, to music by Cesare Pugni. The old one-act work presented a variety of characters who disguise themselves as tree nymphs. The Imaginary Dryads can have been anything from a subtle comedy to a joyous romp or something in between. Lubov played the Young Baroness. After the Danse des Dryades and the Grand Adagio, Lubov danced the last in a string of six variations – always an honorary place in ballet. As spiritual creatures, the dryads, fake or not, should have played to the girls’ allegro talent with airy steps, while the plot served to explore their comical side, needed for future roles like Gulnara, The White Cat, Swanilda, the Dance Manu and the Lises from La Fille mal Gardee and The Magic Flute. There’s no doubt that Gerdt, Petipa and the directorate were aware of that year’s potential.

Ten days later Lubov was at the Mariinsky, to show herself with the company. The occasion was a benefit performance for the corps de ballet. Together with Pavlova, Belinskaya and Makarova-Yuneva, she danced the pas de quatre from the old ballet Trilby, inserted in the comical Cavalry Halt. Petipa had created it on his buxom daughter Maria - who metaphorically works her way through the ranks of a cavalry. The formula had met approval the year before, when Fokine and Obukhov danced a specially devised pas de quatre in Paquita with Sedova and Egorova from Cecchètti’s class. Within Trilby’s frame, Gerdt, following Petipa, created variations that stylistically differed so as to present each of the girls most advantageously. The formidable critic Nicolai Bezobrazov commented about Pavlova and Petipa’s ‘... good schooling and exceptional ballon ...’ The whole process around his daughter’s debut gripped Petipa to the extent that, as Nicolai Legat recalled, the ballet master urged him to choreograph a pas de deux for Lubov - too nervous to accomplish it himself: “... I want big success. You dance with Lubov. You set dance ...”

The Mariinsky

Right before the century’s final summer, Lubov and Pavlova joined the company as coryphées on an annual salary of 800 rubles. During a portrait session, the fresh coryphées were reunited in front of the camera. A situation akin to The Magic Fairy Tale occurred: while sitting opposite of one another, Pavlova tried out some cordial smiles, but Lubov’s expression remained enigmatic, even a little antagonistic. The pictures exude forced friendliness at best.

Other joining graduates of that year included Belinskaya, Andrianova, Makarova-Yuneva, Vasily Stukolkin and Sergei Ulanov, whose case, incidentally, is the opposite of Lubov’s: he is singularly remembered for being someone’s father, the Soviet ballerina Galina Ulanova. The group were the first to enter the company under the directorship of Prince Sergei Volkonsky. At 39, he could be considered young for the post, but his age might have been perceived as to guarantee the upcoming century’s salutary changes. Volkonsky’s predecessor was Ivan Vsevolozhsky. Despite being his uncle, Vsevolozhsky failed to prepare his nephew for what awaited him, about which later. Starting with Volkonsky’s tenure, the Mariinsky’s staid casting policy began to shift somewhat. Role-owning in general endured, but younger dancers were given opportunities sooner. Since the school had recently produced Sedova, Egorova, Fokine and Obukhov and now Pavlova, Belinskaya - and Lubov, this move was far from misplaced.

A freer hand was also grist to the mill for Petipa where his daughter was concerned. The master was an octogenarian before long and he knew it. Determined to see at least one of his daughters make ballerina during his lifetime, he distributed her in solo and principal parts with unprecedented speed – e. g. what Matilda Kschessinskaya had achieved in her first season came nowhere near Lubov. Word to the world that Petipa had a daughter who could do it.

Lubov’s older sisters Maria and Nadezhda were known in the theatre as Petipa 1 and 2, meaning she would henceforth be Petipa 3.1 Petipa 3 would embark on what proved to be among the most promising dance careers - and the shortest ones.

Lubov had summered in Milan, to take class with the famed Caterina Beretta - Pierina Legnani’s teacher. So, she was in super-shape when 1899/1900 kicked off on 5 September with a double bill: a single act from Lev Ivanov’s Oriental fantasy Mikado’s Daughter and the Romantic evergreen Giselle. Lubov was on immediately. Her initial assignment was in itself a manageable one: the demi-solo role of Zulme. The attendant Wilis Moyna and Zulme each have a short variation within the Pas des Wilis, a long number performed near Giselle’s grave that builds up in intensity. For any dynamic dancer Zulme is a feast, with cabrioles (nowadays assemblés entournant) and renversés as hallmark steps. Lubov’s real challenge should have lied in all that came with Zulme: entering Russia and the world’s most prestigious ballet company, bypassing the corps de ballet.

And then it happened. No less than three weeks later, Lubov debuted as Myrthe, the Queen of the Wilis. She had to muster her forces for this one. While a strong jump is a plus for Zulme, it is a prerequisite for Myrthe’s variations: for every second the ballerina spends on the ground, she spends two in the air. So, even when possessing an elevation like Lubov’s, the role was - and remains - a challenge. Apart from possible stamina issues, there was the authority aspect; Lubov had to command the experienced corps de ballet and the guesting ballerina, Henrietta Grimaldi. It was a daunting prospect, no matter who her father was - or maybe more so because of that. Natalia Roslavleva wrote: ‘... old Petipa hoped for the success of his daughter in the role of Myrthe, Queen of the Wilis ...’ The denotation was given in comparison to Pavlova, ‘... on whom all the balletomanes’ binoculars were focussed ... ‘

Roslavleva refers to Pavlova’s Zulme, who received the role after Lubov’s two-performance stint. Her observation smacks of a negationism that alludes to Pavlova’s later fame. The omnipresent balletomanes were definitely following the new recruit Pavlova, but no less so the new recruit Petipa 3, here in a principal role - besides, as Myrthe, Moyna and Zulme don’t get in each other’s way variation-wise, there was no need to divide the attention.

A next job of note for Lubov was Fleur-de-Farine, one of the Prologue Fairies of Sleeping Beauty. Most of the cast were first-time gatherers around Aurora’s cradle: Pavlova as Candide, Sedova as Violante, Vera Trefilova as Breadcrumb and Vera Mosolova - a former Candide - as Canary. The last two dancers replaced the remaining members of the original cast, Klavdia Kulichevskaya and Anna Johanson. All the girls would keep their roles during Beauty’s subsequent performances of that season. Lubov ‘inherited’ Fleur-de-Farine from Olga Preobrazhenskaya, who was slowly but surely moving on to ballerina roles.

The revival of the Romantic ballet Esmeralda was due shortly and, on that evening, 21 November, Kschessinskaya danced the titular gypsy. Lubov and Pavlova danced the two friends to Preobrazhenskaya’s Fleur-de-Lys, the soon-to-be-abandoned fiancée of Esmeralda’s love interest Phoebus. The trio led a large corps de ballet in the Grand Pas des Corbeilles, each with a variation. Critics observed how Pavlova 2 and Petipa 3 had an element of competition, displaying much effort. Alexander Plescheyev noted how ‘the latter gained the greater victory.’

The matinee of 31 December was The Hump-backed Horse, the final performance of the 1800s. Legnani, Alexander Shiryaev, Gerdt and Felix Kschessinsky starred. The old Russian tale was, both in treatment and casting, a microcosm of what the Imperial Ballet had achieved during the 19th century, but the century’s turn was not marked by a premiere or a gala (on 2 January there was Esmeralda - business as usual). As anyone who has experienced a turn of the century can confirm, it is an event that leads to reviewing one’s wishes and goals, even if only momentarily. For Lubov, as a sensitive young woman in a sought-after profession in a sought-after company, this can hardly have differed. Did someone come up to her after the big toast, saying ‘a penny for your thoughts,’ making her gasp and almost spill the rest of her champagne?

Lubov’s Rise

During the subsequent half of the season, Lubov was given more opportunities. Her father, moaning, ailing, chain-smoking, yet unstoppable, was to create no less than three ballets in a row: the one-act The Trials of Damis and The Seasons, and the two-act Harlequinade. All were first given in the exquisite Hermitage Theatre, part of the Winter Palace complex. Lubov was cast in all three ballets. The first, The Trials of Damis, premiered on 17 January. In the Watteau-inspired ballet, Lubov found herself again surrounded by experienced soloists: Preobrazhenskaya, her Giselle to her last Myrthe, Varvara Rikhlyakova, Sergei Lukyanov, the virtuoso dancer Georgy Kyaksht and others. They presented a travelling theatre troupe with a marionette routine. Lubov danced with Gorsky, who had created Clorinda on her. He left St Petersburg to take up the ballet master tasks of Moscow’s Imperial Ballet. Dancer Nicolai Soliannikov asserted that the puppet choreography stood out. Once ‘Damis’ reached the Mariinsky, this part was well received by the patrons, unlike the rest of the ballet and its 18th-century style dances, which they deemed a bore.

On 23 January, Pierina Legnani had her benefit performance. For this one, the Italian star had endeavoured to have The Pearl represented. Now consigned to oblivion, The Pearl must count among the most important pièces d’occasion that ever graced a (Russian) stage, as it was the coronation ballet for Nicholas II. When added to the regular repertoire, its scale required adaptation for the Mariinsky, although that was a venue not too small in itself and used to accommodate off-stage choruses and orchestras. While Legnani herself shone again as The White Pearl, Lubov led the dance of the pearls with five other girls. They had lost the adjective ‘white’ somewhere along the Moscow-Petersburg transfer. The Pearl followed The Trials of Damis, but the evening was not over for Lubov. The 2nd act of the Ivanov/Cecchètti ballet Cinderella, by then rarely seen, was billed. The Ball Act provided many dance opportunities, and Lubov was partnered by Kyaksht leading a pas de six: dancing behind Lubov were her forgotten classmates Belinskaya, Elpe and Makarova-Yuneva, along with Agrippina Vaganova, not forgotten. The pas de six was not listed for Cinderella’s premiere (1893), and it is safe to assume that it was an insertion for this particular occasion, presumably by Ivanov or the Legat Brothers. Lubov’s spot of prominence bore Legnani’s stamp of approval, for it was her evening.2

The second Hermitage premiere, the allegorical ballet The Seasons, was given on 7 February. The Seasons boasted another score by Alexander Glazunov. Lubov came out in the opening section, Winter. Winter itself was impersonated by the charismatic, icy-blue eyed Alexei Bulgakov, and there were four soloists in his retinue with a short, frozen water-themed variation. Pavlova danced the first, Hoarfrost, then Sedova, Ice, Trefilova followed as Hail, and Petipa 3 concluded as Snow. The variations were diligently recorded by Preobrazhenskaya, but her notes are not public. Of the four, Snow is the most traditional. It is a cavatina, sentimental, as if written for a barrel organ. When exploring descriptions of Lubov’s work and the obtainable role information, a picture of an allegro dancer emerges, equally at home in speed-requiring material and grand, ground-covering movement. With Snow, Petipa either sought to tap into Lubov’s thus far hidden lyricism, or had Snow function as an etude to practise dancing lyrically, before graduating into the ballerina roles she needed it for.

Of the said three premieres, the last is still ‘alive’ today: on 10 February, audiences - or actually a privileged part of it - got acquainted with Petipa’s Harlequinade. Lubov and her peers appeared before the court in The Serenade, supporting Kyaksht’s Harlequin as he wooed Kschessinskaya’s Columbine.

Three days on, that same Kschessinskaya had her benefit performance. In her autobiography, the prima ballerina writes that she opted to bill ‘the two ballets which I had just danced.’ Going by these choices, Harlequinade and The Seasons, one should assume that her relationship with Petipa was not strained at the time (as it became later), and especially so because the diva allowed Petipa 3 a pas de deux with Mikhail Fokine in the final divertissement.3 Lubov was, however, taken out of Harlequinade’s supporting couples and replaced by Pavlova. It seems an understandable decision, as she had initially been cast in every part of the evening. This way, Kschessinskaya ensured that her benefit did not run a little Petipa 3 sideshow, without depriving Lubov of a chance to shine.

The divertissement also featured Lubov’s half-sister Maria, who performed a Russian Dance with Nicolai Legat, a duet called Valse Fantaisie (credibly Glinka’s) danced by the pair Mosolova and Obukhov, while Preobrazhenskaya contributed her Matelot. The beneficiary herself graced the stage in (an) Aragonaise, (here) a pas de trois with Shiryaev and her brother Iosif, who had arranged the number. For Lubov lay a thrilling and daunting a task ahead, doing a classical pas de deux while the experienced ballerinas performing trifles. Of course, this did not happen by accident. Kschessinskaya had, indubitably, no wish to stay behind in her self-created, benevolent-fairy race when Legnani had so generously given Lubov a chance; she had to top her rival’s pas de six with a pas de deux. If anything, machinations like this evidenced Lubov’s promise and progress.

According to Kschessinskaya, crowds thronged the stage door; gallery regulars and students, who ‘... came to pay a worthy farewell to their idols, especially those of the fairer sex ...’ Although admirers of Petipa 3 did not yet conjure up a chair to put her into and transport her ‘cheeringly’ to her carriage - as Kschessinskaya claimed hers did, no doubt some stood there awaiting Lubov. One can imagine the effect it had on an impressionable young dancer after such a spot of prominence and moreover, a girl whose ideals reached beyond dancing. It is tempting to think that one of the stage-door Johnnys was a certain Vyacheslav Teofilovich Putsikovich.

On 16 April 1900, Petipa 3 danced Flora in The Awakening of Flora. It was Lubov’s first major ballerina role; the character around whom the narrative evolved. Belonging to Petipa’s Anacreontic series, Flora was his answer to a beloved art subject: the romance of the flower goddess Flora and the west wind Zephyr. In Petipa’s version, a plethora of other deities were met. Five years to the date had passed since Flora was last seen at the Mariinsky (not counting Peterhof). It can’t have been a coincidence: Volkonsky and Petipa should have contrived this little anniversary,’ catering to the balletomanes, those sticklers for dates. Kschessinskaya had been the original Flora, and hers were big shoes to fill. Lubov was partnered by Nicolai Legat as Zephyr and her former teacher Gerdt as Apollo, while the Aurora dancing beside her in the waltz was Pavlova.

After her debut, Lubov did Flora’s two remaining performances of the season. Vera writes enthusiastically about her sister’s achievements, but so did the stern critic Konstantin Skalkovsky: ‘… Mme. Petipa is a scion of the artistic family that has been working with honour and glory in the choreographic industry for two centuries [sic]. Her debut can be considered a success and Mme. Petipa is grateful to her teacher, Mr. Gerdt, who partnered her in the pas d’action, that touchstone of ballerina-hood. Mme. Petipa possesses, apart from an exemplary schooling, everything a great dancer needs, a slim figure, shapely legs, lightness and conviction. She additionally performed a waltz and a grand pas, all strictly classical of style, to great acclaim …’

If Petipa 3 had botched it up, Flora would have represented her father’s failed gamble and awaited shelf-life. Now the ballet returned for another three performances in 1900/01, securing an extended leash on life for many years to come. Interestingly, when Skalkovsky described Lubov’s figure and talent, he really re-described his friend Varvara Nikitina. The ballerina left the theatre after feeling undervalued in 1893. Lubov closed the season with Flora, but preceded that with The Nutcracker on the same evening. Together with Egorova, Pavlova and Sedova, she was a soloist in the Golden Waltz (Flower Waltz). In all, Petipa 3 danced 32 times in 10 ballets and 4 times in one opera. When looking back on her remarkable season, Lubov could be exhilarated and ready for the next after a well-earned summer holiday. Only, if she had been exhilarated and ready, she did not act on it. On the contrary.

Final Performance

1900/01 opened on 3 September, with Bluebeard on the playbill. The ballet-féerie, back after two seasons, displayed a new cast: Preobrazhenskaya, the original Anna, danced Ysaure now, and Petipa 3 her sister Anna as well as Venus (Act III), her second interpretation of the love goddess after The Two Stars.4 Within 24 hours after curtain-up, two major things had taken place: Preobrazhenskaya was officially hailed as Ballerina, and Petipa 3 was no longer a member of the Imperial Ballet.

Old questions pop up. Did Lubov decide to leave in an impulse, after the performance? Before? Or … during? For Preobrazhenskaya’s promotion between Act II and Act III may have pushed her to accelerate matters. Here is a dramatisation of how it could have come to pass:

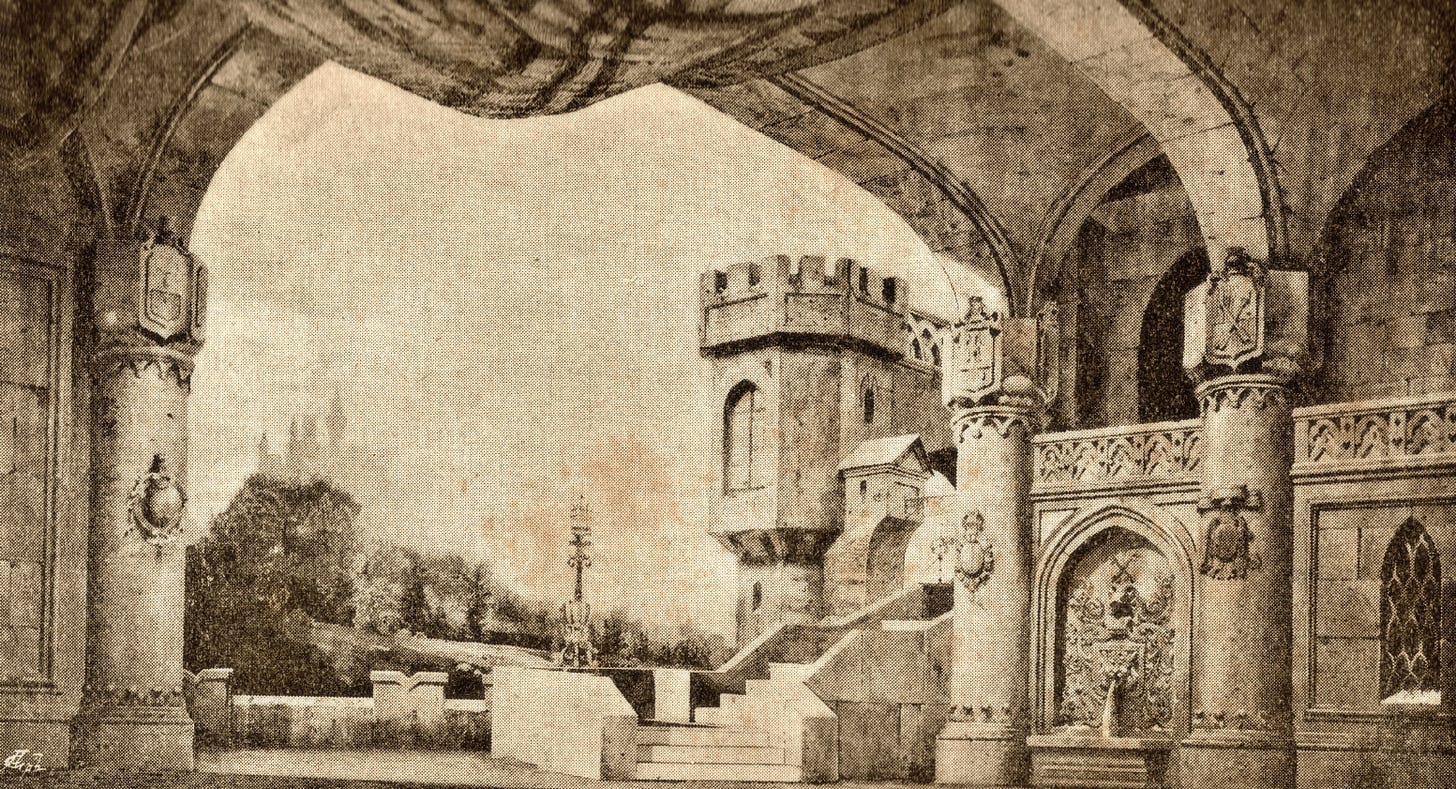

The Mariinsky auditorium resounds with applause as the curtain comes down on the calls for Act II. Moments ago, an effective coup de théãtre exposed Bluebeard’s dark secret: a femicide fetish. Preobrazhenskaya, as Ysaure, makes her way from the stage with wide, turned-out steps, as tired dancers do, listlessly responding to back pats. Stagehands fly out the stuffed female corpses with amused smirks, uttering risqué banter. Behind the false proscenium with the horror room, the castle terrace set is already in place.

Lubov, meanwhile, sat in her dressing room. Because her character, Anna, plays no part in the wonder-chambers sequence, there was ample time to change. It is about twenty minutes to the 3rd act, and after being helped into her next gown, Lubov checks herself in the mirror, thanks her dresser routinely and goes to the stage. As she walks through the corridor, she goes through her gestures of the upcoming Mime Scène. With everything that is going on in her personal life, she finds it hard to act Anna and her worrying about ‘her sister’s’ peril. She focusses on her minute act of rebellion: when grabbing the blood-stained key from Ysaure, she will hold it higher and longer up, for everyone to see – why did they make it so small? Not a soul beyond the closest stalls rows ever registers the blood on the metal.

Content with her solution, Lubov approaches the wings and hears excited voices. The stage manager ushers her on stage, where she finds all her colleagues. She passes Kyaksht, who is practising pirouettes. Pavel Gerdt talks to Lev Ivanov at some distance from her. Lubov frowns; she doesn’t recall Ivanov being on duty, at least she did not see him earlier on. She wonders what is going on. While Gerdt gesticulates to the pale Lev Ivanovich, his jaw makes his bluish beard move up and down. Ivanov, with his hands in his pockets, nods his head. Lubov realises that Pavel Andreyevich perceives this as Ivanov agreeing with him. She chuckles. Her musketeer-like ‘brothers’ are there too: Iosif Kschessinsky shares a laugh with two girls of the Valse des Étoiles, while Ivan Kusov absentmindedly plucks at the tip of his épée. Nicolai Legat treats Lubov to his impish grin. He will be Mars to her Venus later on. He is not yet in costume, but the long baroque wig already covers his baldness. The attached helmet is, necessarily, lighter than it looks. Legat points to the plumes and bobs his head like a big flightless bird. Lubov cannot help but smile, which is what he was after. Her father has left his usual spot and stands amidst them all. Then Volkonsky enters. All the men in charge wear their court attire. Well, well. Volkonsky looks at Petipa, greets him briskly and walks to Preobrazhenskaya, who stands centre stage. She sports a long, off-white frock - Ysaure’s Scene 6 costume. Her expression is excited, but also a bit unsure. After a short speech to the company, Volkonsky addresses himself directly at Preobrazhenskaya and announces her promotion. As of this moment, she can call herself ballerina. Applause, cheers, congratulations. Tears. Kisses. Lubov embraces Olga Iosifovna somewhat woodenly, being aghast. Naturally, she is happy for her, but it is not about that. More than ever, she realises that the efforts of those around her are aimed at her making the highest grade in ballet as well. This scene will take place again in the not too distant future and then she, Petipa 3, will be where Preobrazhenskaya is now. But is that what she truly wants? To be a queen in this world? A future of her own design and desire, for which arrangements are in place, now overwrites any second thoughts about staying on.

Act III begins. Lubov, afraid that someone will detect her inner turmoil, slightly overacts to Preobrazhenskaya’s Ysaure when shown the key; the proof of her disobedience. She completely forgets to hold it up high before hurrying to the fountain to wash the blood off. Ysaure’s real love, the page Arthur, runs off to fetch help - so Sergei Legat exits. Lubov mimes the gestures that comfort and then lament Preobrazhenskaya, whose Ysaure is about to be killed. While Gerdt fetches with his sword, Lubov climbs the turret to look if the brothers are on their way. There is the distant castle; her character Anna sees her ancestral home. Does Lubov see her own at that moment? “... salut! demeure chaste et pure ...”5 Especially as a half-French dancer in a time and age where narrative and symbolism in ballet reigned, the Faust analogy cannot have escaped her ...

Resignation

For a woman to simply pack up and clear out, encouraged to take time and contemplate the prospects, was not something the dawn of the 20th century had on offer. The right to pursue an individual lifestyle was not high on the Russian agenda then, and not for a long time to come. Lubov’s single available option was marriage, and the circumstances had made her vulnerable to any offer that came her way - embellished with romance and promise of love, or even without them.

And so it happened that Vazem wrote about the episode that Lubov ‘... left the theatre having rushed into marriage ...’ Genealogy and civil records mention 27 September 1900 as the wedding date. It is not clear whether pre-revolutionary archives were digitally amended to the Georgian Calendar, but all date-related scenarios rule out that Lubov’s marriage took place before she quit the Mariinsky.

When did Lubov impart her intentions, and to whom? Was not only her retirement, but an engagement, or even a husband, a surprise for her nearest and dearest too - as Vera seemed to suggest it was? There is also no answer as to when Lubov met her spouse, Vyacheslav Putsikovich, and what role he played in her retirement.

Putsikovich was a year older than Lubov, and the genealogy records state that he was a member of the nobility through his mother Ekaterina Georgievna – odd, because that was exclusively inherited through the male line. The groom’s father, Teofil Putsikovich, had died a year before the marriage. He was a writer, but in the civil record he appears as a provincial council secretary. The positions need not necessarily contradict.

But where did all this leave the father of the bride? Petipa, a temperamental man in his younger days, might have chased Lubov away in fury or coldly dismissed her if the situation had occurred then. Now it was no longer in the ageing Petipa’s character to do either, hurt though he was. Moreover, we should note again how much he had invested in producing a ballerina ‘of his own.’ It must have dawned to Petipa that his youngest, Vera, would make an average second soloist at best; ergo, he wanted the door to Lubov remain open as long as possible. Nevertheless, if he knew about Lubov’s plans, would he have bothered to let her prepare for the important roles in Bluebeard? Did Lubov, in turn, mean to stay on until she had danced them, as a farewell gift to her father? Or could she simply not find the courage to enlighten him and went with it?

Of course, Lubov’s qualms started to build up much earlier. Did spiteful colleagues snipe at her, telling her that the speed of her progress was something they could only dream about? Yet if Lubov was bullied, Vera would have hinted upon that, besides, she knew this was part of the game since her earliest days. Another possibility, that a love-struck Lubov parted from a cherished career in ‘Red Shoes fashion’ is difficult to believe as well. The reason can be found in Vera’s following observation: ‘... did we children love ballet? Yes, but certainly not indefinitely. If some of us loved it wholeheartedly, it would have to be just Maria and Evgenia, oh, how the others wished they could love it that much …’

Petipa’s ardent wish for his daughters to pursue a dance career was the singular aspect where Vera expressed a mild criticism about her father. She and her sisters had an avid desire to please him, and the place to gain his love was the ballet class. Petipa fuelled these sensibilities - we are left to fill in for ourselves whether he did so consciously or not. What follows is that Lubov felt pressurised by the number of roles thrown at her. If her enthusiasm had increased or stabilised during her career, Vera would have happily altered her memoirs in this respect. The bottom line is that if Lubov’s heart and soul was in dance, she could have coped with every possible obstacle.

Cautiously concluding, influenced by Putsikovich or not, Lubov did intend to stop dancing in the near future and was already a fiancée during Bluebeard. However, the way she ran off after that Bluebeard performance bears the marks of breaking under the strain. The timing of her leaving in relation to The Awakening of Flora is indicative here. If she loved doing Flora, she would have stayed two weeks longer and so dance her twice more, for the ballet was scheduled on 10 and 27 September (and include another Anna/Venus to boot), or leave after Flora’s December performance. Or simply finish the season.

Replacing Lubov

The September repertoire seems to have been designed with one eye to Petipa 3, so she must have caused quite the hassle, e. g. the time her action left Pavlova with to prepare for Flora, a week on the nose after her last performance, and learn Anna/Venus6 for the next Bluebeard, a week after Flora in turn. The whole episode puts Pavlova’s rather celebrated journey into Flora in a different light. Petipa cannot have welcomed her doing it, as he had envisioned Lubov to star in the role for many years to come.

Because of the unobserved notice period, the management and Lubov cannot have parted friends - officially. Volkonsky though, should have sympathised privately, if not expressly, estimating Lubov and he were similar creatures. They had started out together and both had not taken to their jobs. The story of Volkonsky’s dismissal, directly or indirectly caused by Kschessinskaya - depending on how far one wishes to apply cause and effect - still resonates. The noise of Lubov’s departure, however, has long since abated.

While he had to come to terms with the fact that Petipa 3 was no more,6 Petipa unexpectedly did get a daughter dancing a full-length ballerina role. On 24 September, Le Roi Candaule was danced by … Petipa 1. Way past her prime and completely out of genre, Maria went for Nisia because Parisian guest star Lina Campana was cancelled. Maria’s casting has a last-minute feel, she learned Nisia in two rehearsals (Irina Boglacheva).7 As Petipa, mocked by the gods, let Maria prepare for the treacherous queen, altering and cutting steps8 Lubov could execute gorgeously, the saying ‘... be careful what you wish for ...’ should have crossed his mind.

Post-dancing Years

As far as can be told, the second half of Lubov’s existence consisted solely of family life. She and Putsikovich had two children: Lubov (b 1905) and Lydia (b 1908). Information on her becomes scarce here. In Petipa’s available diaries, Lubov appears in just one entry (17 Sep 1903), when he mentions the Name Day of his wife, Nadezhda, Lubov and Vera.9 From the fact that the eldest Putsikovich child was named Lubov (Vyacheslavovna) too, can be gleaned that the relationship of Lubov and her parents had been rekindled since her life-changing decision. And indeed, when Petipa later on complained about losing the love of his family, he excepts Lubov.

Sadly, Lubov’s new life did not bring the happiness she craved. While endeavouring to make a home, she might have begun to romanticise the more carefree aspects of dance on occasion - read miss it. After all, there were times she went for it, and was ‘driven,’ as Vera stated she could be. Nevertheless, Lubov, catering and sensitive to the needs of those around her, must have hidden those regrets, as there was no way back. But there was more. Sorrow, even suffering. We learn about this through Vera again, yet what exactly brought that about is vague.

However, two things on the subject stand out in Vera’s memoirs, the first being ‘... She got married hastily ...’ If all had been bliss, would Vera, decades on, have used that adjective? A match made in heaven would have nullified any hastiness.

The second: ‘… My two nieces that are alive today wear their grandfather’s name proudly, both delivered their contribution to the [...] Russian theatre …’ Vera refers to the two daughters of Nadezhda. Vera died in 1961, which means that neither of Lubov’s girls reached their sixties. We know this for certain of Lydia, whose married name was Kapmar, as she died in 1948. The genealogy records give no details on her older sister. So, did Lubov’s misery involve her daughter Lubov Vyacheslavovna?

In 1913, Lubov turned to the theatre to apply for a pension. She was denied on grounds of her limited time of service; one year and three months. Not incomprehensible. Lubov was without a doubt aware of her chances, but the circumstances must have forced her to swallow her pride. The submission could indicate that the couple were out of money, that Lubov was a divorcee, or mean that Putsikovich had died. So far, this unfortunate episode is the last record of Lubov alive. Trapped between familial expectations and her own ideals during the first part of her existence, then spending the second half of it in misery and possibly regret, Lubov Putsikovich, Lubov Petipa, Petipa 3, died in 1917, aged 37, racked by a heavy life.

Postscript

Incidentally, Lubov’s gifted classmates, Stanislava Belinskaya and Anna Pavlova, were also not destined to die old ladies. Ill-health curtailed Belinskaya’s dancing days. Like Lubov, she left the company early on. She died aged 36. Pavlova passed away short before her 50th birthday, but not after dragging a not overly suitable physique through a career that in length, fame and achievement made up handsomely for the lean statistics of her poor peers.

Lubov’s name pops up seldomly, therefore it is worth mentioning a 1968 letter from Sergei Grigoriev, her one-time colleague and régisseur for Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes, to writer Yuri Slonimsky, wherein he called Lubov a good soloist.

But let’s shift a long time back, to 25 years before Lubov departed this world. It is 25 August 1892, and we find the Petipas at the deathbed of Evgenia. Evgenia is the sister closest to Lubov in age, the daughter on whom Petipa had pinned his artistic hope for the future. But it is over. Does young Lubov, that ‘rare soul,’ now resolve to fulfil that hope, driven by love for her father? To do the job for her sister? If so, she denied herself until she could no longer live a lie. That understanding coincided with coming across a man she allowed to make her his wife. The thought that Lubov willed her career to flare up from the embers of Evgenia’s promise lingers.

© Peter Koppers

Notes

1) Similarly, Anna Pavlova became Pavlova 2 because of the corps de ballet dancer Varvara Pavlova.

2) Benefits had a far more personal approach than normal performances understandably could be. Beneficiaries had a say in the casting and programming.

3) Details of this pas de deux are unknown.

4) The Venus casting for Bluebeard is in many cases omitted from the available records, but when Preobrazhenskaya took over Venus from Kschessinskaya (effective at latest on 29 Jan 1897), Anna and Venus were combined. It is highly unlikely that Petipa would have re-separated the roles for his daughter’s debut. The date of Pavlova’s first Venus is recorded: 17 Sep 1900 and on 3 Sep, she was still listed for the Fin-de-Siècle Polka.

5) Cited from Gounod’s Faust, an opera Lubov would have been familiar with.

6) The name Petipa 3 was revived through Vera when she joined the Imperial Ballet, a few years on.

7) Lina Campana’s ‘default was never explained’ (Wiley), but Irina Boglacheva asserts illness. This conforms to her two rehearsal-theory. The last Nisia, Lydia Nelidova, was unavailable and workhorse Preobrazhenskaya had been busy with Ysaure, Coppelia and The Nutcracker. Legnani and Kschessinskaya were not back yet - insofar they would have consented to dance Nisia (on such short notice). Lubov Petipa probably could have done it.

8) Maria Petipa was partnered by her lover Sergei Legat as Gyges. Legat was a budding choreographer, and chances are that Petipa left the tinkering with Maria’s steps to him.

9) There are other diary entries in which the name ‘Luba’ appears, but from the context can be gleaned that Petipa refers to his wife there (in other places he uses ‘my wife,’ hence the confusion). After Russia adopted the Georgian Calendar (1918), the Day of the Remembrance of the Martyrs Faith, Hope, Love and their mother Sofia, is celebrated on 30 September.

Sources & Bibliography

Sergey Belenky

Andrew Foster

Doug Fullington

Sergey Konaev

Anna Pavlova, N Golovko, etc.

Anna Pavlova Her Life and Art, Keith Money

Anna Pavlova, Pages From The Life Of A Russian Dancer - Vera Krasovskaya

Artists of the Imperial Ballet in the 19th century, Irina Boglacheva

Biographies and Memoirs / Ballerinas, Valeria Nosova

Dancing in Petersburg, The Memoirs of Kschessinska, Translated by Arnold Haskell

Era of the Russian Ballet, Natalia Roslavleva

Faust, Jules Barbier & Michel Carré

Fund Guide on Manuscripts and Documents (Putevoditel’ po fondu “Rukapi i Dokumentii), St Petersburg Theatre Museum, T Vlasova etc.

Leader of the Russian Ballet, Nicolai Soliannikov*

Olga Preobrazhenskaya, A Portrait, Elvira Roné

Our Family, Vera Petipa*

Materials for the History of Russian Ballet vol. II, Mikhail Borisoglebsky

Mikhail Fokine, N Teofanov etc.

My Reminiscences, Prince Serge Wolkonsky

Pavlova, John and Roberta Lazzarini

Russian Ballet Theatre at the Beginning of the 20th Century (Russkii Baletnyi Teatre Nachala XX Veka), Vera Krasovskaya

Sixty Years in Ballet (Shest’desyat let v balete), Fyodor Lopukhov

The Greatest Russian Dancers, Gennady Smakov

The State Theatre Library Museum of St Petersburg

The Story of the Russian School, Nicolai Legat

Two Essays on Stepanov Dance Notation by Alexander Gorsky, Roland John Wiley

* From Marius Petipa, Meister des klassischen Ballets, Eberhard Rebling, Petipa Materials.

Photo Credits

A.A. Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum, Artchive, Bolshoi Archive, St Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music / Санкт-Петербургского государственного музея театрального и музыкального искусства, St Petersburg State Theatre Library / Санкт-Петербургская государственная театральная библиотека, Mariinsky Theatre Archive, Photo Collection of Peter Koppers, Salvador Sasot Sellart