Petipa's Bluebeard

‘Hang ’em While You can!’

(All pre-1918 Russian Dates are given Old Style)

Introduction

More and more, ballet culture moves past thinking that Sleeping Beauty is an all-you-need microcosm of Petipa’s Imperial Ballet, as a complete picture of his art arises with reconstructions of other work. Alas, some can never be added to that list because they are not or scantly notated. Still, writing about them creates their ‘negative contours,’ adding to that complete picture too. With Bluebeard, we have stumbled on just about the hugest negative.

Origins

‘… I arrived in Petersburg [in 1847] on a steamer - there were no railroads back then […]’1

On 8 December 1896, the fairy tale Bluebeard was given a new incarnation. Marius Petipa choreographed the ballet in honour of his (upcoming) jubilee. Parallel to Bluebeard’s preparations, Petipa started to write his memoirs. So, while letting people dance Perrault, he let his mind wander.

‘… In those days, customs inspection of travellers took place on the English Embankment, through the present Nikolaev Bridge, which did not yet exist either. The weather was frightfully hot, I was perspiring bucket loads ...’

A few weeks later, in 1897, the venerated ballet master would be 50 years in Russian imperial service. A partly publication of the memoirs accompanied the festivities.

‘…We had to go to a hotel after we were cleared. Then I remembered my hat - it wasn’t there.

Searching led to nothing […] Disgruntled by this loss and fearing sunstroke, I tied a kerchief around my head. The next day, I went to the all-mighty Director of the Imperial Theatres, Alexander Gedeonov. He received me very courteously …’

1897 was also the 200th anniversary of Charles Perrault's Barble-bleue. The ballet was based on his 1697 tale (based on an older version in turn). It had been published in a collection that won worldwide acclaim as Les Contes de Ma Mère l' Oye - initially just an extra title, printed on the spine.

Gedeonov: ‘… The season here begins only in September, so you are free until then ... Should you need money, however, tomorrow you will be paid an advance of 200 rubles...’

Petipa: ‘… at that point - I recall this as if it were now - spontaneously blurted out: “My God, what a place have I come to! This must be heaven! I want to stay here the rest of my life!” I did not suspect that these words would be prophetic ...’

Exhibit A of this being prophetic: Bluebeard, a huge undertaking in 3 acts, 7 scenes and an Apotheosis. Petipa’s take on it continued the genre called ballet-féerie, a brainchild of director Ivan Vsevolozhsky. This type of ballet, inspired by the operetta-like féerie - regularly seen in the capital - had originated with The Magic Pills (1886). It celebrated the company’s installation at the Mariinsky Theatre. The ballet-féerie is, of course, best known for Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker. The genre lived longer than one might think, at least until Serge Lifar's Les Mirages (1947); subtitled ‘Féerie chorégraphique.’

The genre often comprised fairy tales. Their morals and spunky characters proved to be well-suited to ballet. Where desired, occurrences could be pushed to the libretto’s fringes, emitted through mime or happen off stage, not much different from Shakespeare characters referring to off-stage happenings, battles, etc. Divertissements, dances in the style of the narrative, ‘filled the gaps.’ Petipa utilised them expansively. Preceded by Coppelia, the final acts of Sleeping Beauty and Raymonda, inter alia, are nothing if not a large divertissement. As was Bluebeard’s last scene.

A portion of Bluebeard’s divertissements consisted of French dances. Petipa must have revelled in staging dances in the (pseudo-)styles of his native country: Act I had a bourrée, performed by the Theatre School and a Norman dance (with bag pipes and tambourins), Act II a passepied, while Act III boasted a gaillarde, monaco and cotillon. The underground chamber dwellers had a big divertissement devoted to them magical creatures. Fairy tales cannot exist without the supernatural element.

Story

The curtain opens on a splendid garden with an ornate gate and to the right, a corner of the Castle de Renoualle protrudes from the wings. Ysaure de Renoualle, a beautiful young noblewoman, is in love with Arthur, a penniless page in the entourage of Raoul Barbre-bleue (Bluebeard), lord of the neighbouring estate. Arthur and his band enter, to serenade at Ysaure’s window. She comes down and a love scene ensues. Her brothers, Raymond and Ebremard, interrupt the tryst. Arthur quickly dons his mask, but they order him to take it off. They scoff at him; Ysaure is way above his station. Bluebeard is announced. Ysaure is pressured by her brothers into accepting the aged, rich nobleman (the eldest would, of course, intend to install his own future wife as chatelaine in the Renoualle home). The act culminates in a grand pas d’action with Ysaure, her sister Anna, brothers and groom, her two friends and poor Arthur. As soon as the dancing finishes, Bluebeard, mad with love, declares he wishes to proceed with the wedding immediately. Ysaure is outfitted with a veiled tiara, popped onto a sedan and carried inside, to the family church, followed by her party. Arthur is left in the garden. When Ysaure exits on Bluebeard’s arm, he tries to offer his now unattainable beloved a flower, but Anna prevents him from doing so.

In Act II, Ysaure sits in her new, luxurious rooms, making do with her situation. She is being entertained by Anna and Arthur when Bluebeard enters. He has to leave again right away when a knight challenges him to a duel on behalf of his master (this reeks of a scheme, arranged by Bluebeard himself). He invites Ysaure to explore the castle in his absence and hands her the keys to the underground chambers, but threateningly forbids her to open the last one, the one with an iron key. Soon after, Ysaure is led by Curiosity, a statuesque woman complete with ‘eared’ staff, to the mysterious dungeons. She encounters enchanted objects and characters: chamber one contains metals and utensils, chamber two Orientals, and chamber three is all precious stones. But then Ysaure’s curiosity gets the better of her, and she unlocks the door to the forbidden room. To her horror, Ysaure sees something she is ill-prepared for: her predecessors’ bloody remains hanging from the ceiling. Six of them. Ysaure drops key and candle, and faints.

The curtain rises again on a courtyard in Bluebeard’s castle, on the Scene Mimique (Act III, scene 1). Ysaure and Anna hurry to the fountain to cleanse the bloodstained key, but the waterspout, a sinister gargoyle, is an agent of evil. Dreading her husband’s wrath, Ysaure implores Arthur ‘for the sake of God,’ to go and fetch her brothers. He obliges without hesitation, and Anna climbs the tower to look out for them (‘Soeur Anna, ne vois-tu rien venir?’). Bluebeard returns and asks Ysaure for the iron key. He has to wrench it from her trembling hands. The dried blood on the metal betrays Ysaure.2 Bluebeard, livid, is about to execute her, but she entreats him to let her say her prayers and goes up to the gallery. The anxiously awaited Raymond and Ebremard arrive just in time to finish the serial killer. When they compliment Arthur on his rescue mission, the page knows his now-or-never moment has arrived and asks for Ysaure’s hand. The brothers happily consent to it. Ysaure will marry Arthur.

Scene 2 plays out in front of a temple devoted to Saturn. With her first husband’s death, Ysaure inherited his enormous fortune (and is off her brothers’ hands). She hosts a lavish garden party. The first divertissement has an astrological theme, the second evocations of the Past, Present and Future. The Temps Future boasts the final duet, the Pas de Deux Electrique, and the ballet ends in an apotheosis with a sphere, shining from the temple’s inner courtyard.

Background

Bluebeard had made its way to the odea before. For example, Raoul and Ysaure appear in André Grétry’s Raoul Barbe-bleue. The comic, recitative-filled opera premiered in Paris on the eve of the revolution. In 1807, Valberg gave the Imperial Ballet their own Raoul Bluebeard, with music by Grétry and Caterino Cavos. Valberg’s pantomime ballet started with a peasant wedding on the estate of the Marquis de Caribas, Ysaure’s brother (we find the second brother, the Marquis of Carabas, in Grétry and in Perrault’s Puss-in-Boots). He brings her to the Gothic castle of Raoul, who wishes to marry her. She consents, despite being in love with Vergy (the predecessor of Petipa’s Arthur). Vergy visits Ysaure, guised as her ‘sister’ (she has none in this version), wishing to see her a last time (and stays around). Raoul has a servant/confidant, Osman, who begs him not to subject Ysaure to the test of his other wives. But Raoul explains he has to, because an oracle prophesied that his spouse’s curiosity gets him killed. Raoul invites Ysaure to wander the castle, just not enter the forbidden cabinet. Ysaure tells Vergy she is touched by Raoul’s vote of confidence. Raoul leaves after a garden party and Ysaure withdraws. Bored and curious, she goes to the cabinet and opens the door, finding three bloody heads. Vergy, who tried to warn Ysaure about the femicide, picks her up from the floor. ‘The sisters’ try to escape and Osman decides to help them by arranging that Ysaure’s SOS is brought out of the castle. Raoul condemns Ysaure to death, but in the end, Caribas and his men breach the wall. Vergy tears off his dress, bravely duels Raoul and wins.

Valberg’s Raoul was Innocenty (Innocenzo) Buzani, Vassily Gladschev performed the Marquis de Caribas and Evgenia Kolosova Ysaure. The name Ysaure was also used in La Filleule des Fées, a French ballet with Petipa's brother Lucien, and Jacques Offenbach’s Barbe-bleue. Anna, the sister, was found in the book, but merged with Vergy in Grétry and Valberg, as it were.

The creatives of 1896 largely rejected Grétry and Valberg. A few elements were used freely, such as the garden party and the mirror idea: in Grétry, Ysaure sings an aria that precedes Marguerite’s Jewel Song from Faust, and in Valberg she dances coquettishly for a mirror, essaying a new wardrobe. 1896 ‘pulled Vergy and the sister apart,’ with Anna and Arthur both surrounding the heroine. Petipa’s Bluebeard was clearly unmindful of his servant’s sexuality. He was not killed by Arthur, but by the brothers, here plural again. They were probably in need of sympathy points. In Grétry, Vergy warns Ysaure, showing her three paintings of women punished for their curiosity, Lot’s Wife, Pandora and Psyche, while Valberg had memorial portraits of the inquisitive wives. In 1896, the idea culminated in Curiosity.

Authors

Responsible for adapting Bluebeard for Petipa was Lydia Pashkova (1850-1917). Pashkova's name lives on because it is attached to Raymonda. Born Lydia Alexandrovna Glinskaya, she was a well-travelled novelist, catering to French and Russian audiences. Sergey Konaev credits her for being ahead of her time: ‘Her fiction features a new type of woman – independent, well educated, divorced or deliberately unmarried – like Paschkoff herself.’

Her work as a correspondent for the Petersburg Figaro reveals another side of her, a less emancipated one, if you will. Here she specialised in reporting everything that concerned upper-class events: births, balls, weddings - in short, gossip. Perhaps fashionably, she expressed herself in ‘a mixture of Russian and French big-city slang’ (Yuri Slonimsky). Pashkova, rumoured to be a relative of Vsevolozhsky, must have been a colourful lady; Petersburg’s own Salome Otterbourne (from Agatha Christie's Death on the Nile, think Angela Lansbury in the 1978 film adaptation).

But Pashkova wanted more: she had been trying to gain a foothold as a librettist in the Imperial Theatres since 1889. Among her declined proposals was Halim, the Thief of the Crimea, in which an adventurous noblewoman travels through the Crimean Mountains, in search of ‘strong sensations.’ Apparently, it was Petipa himself who barred the door.

Pashkova's mission succeeded when her Cinderella was accepted, plausibly during Petipa’s periodic absences. The ballet was edited by Vsevolozhsky (1893). However, when Pashkova's Raymonda reached the stage in 1898, it was so seriously reworked, first by Vsevolozhsky and then Petipa, that there was little left of her. According to Slonimsky, Pashkova had acquired friends in high places, resulting in her credit as Raymonda's sole writer nonetheless.

If the rumour of Vsevolozhsky being Pashkova's relative is true, the ‘inner-circle friends’ story’ may originate with him to divert attention from himself. But whatever mysterious hold Pashkova had over Vsevolozhsky, with a 15-year age gap between them it is doubtful he fathered her. Considering that Bluebeard preceded Raymonda, it is difficult to tell if, or how far Petipa and Vsevolozhsky went with adapting Pashkova there.

When all is said and done, it should be argued that Pashkova’s style, a straightforward narrative as a platform for dances, was very much suited to the ballet-feérie. Yet critics preferred to use her for target practise. Petersburg Gazette: ‘[…] written in naïve form as if spectators were children ...’ This stance on Pashkova was picked up by the 20th century, the epoch that loftily indulged in librettos based on novels and plays with intricate plotlines. Steps were overloaded with information. Deliberately light is not the same as superficial.

Designs

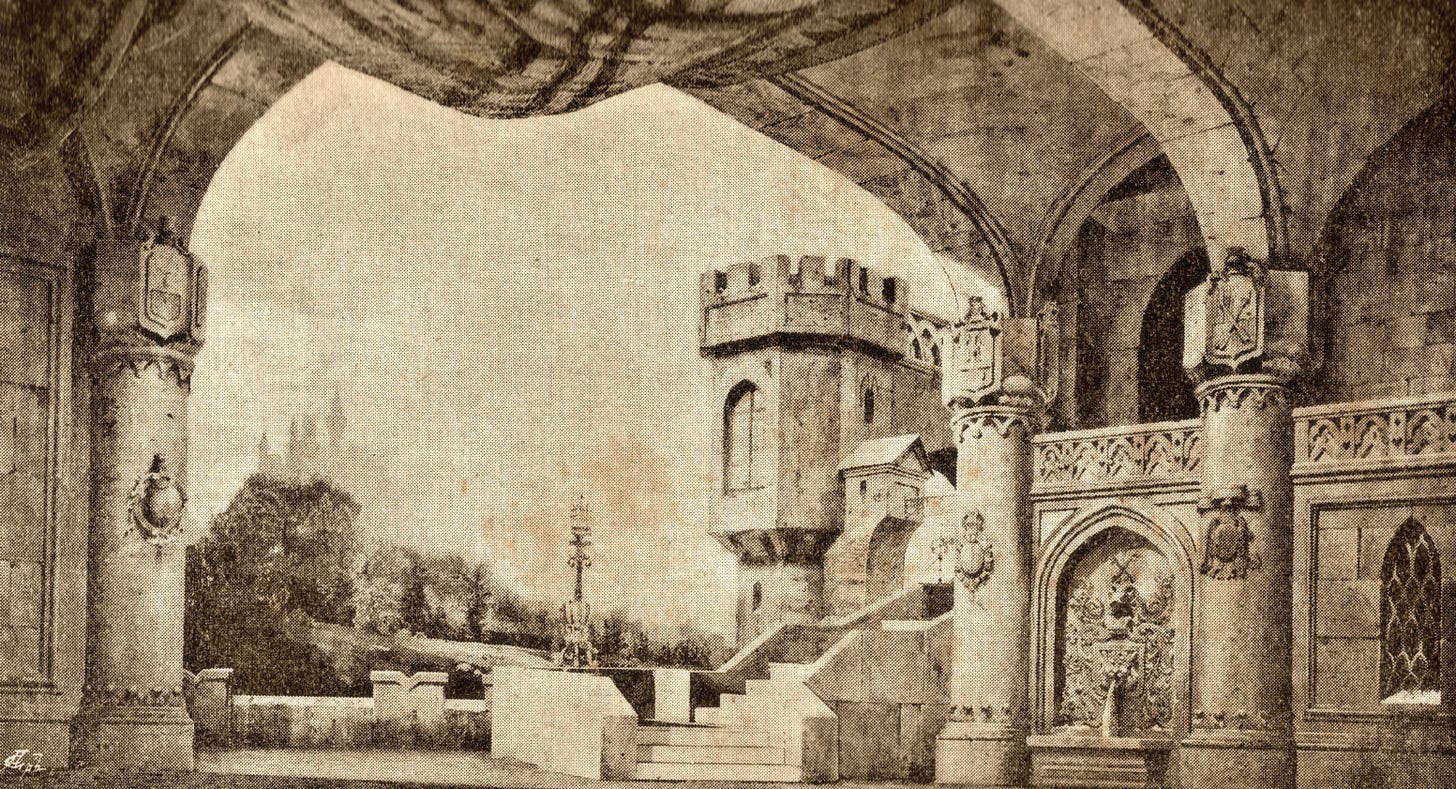

As was de rigueur in the Imperial Theatres, sets for Bluebeard were divided among in-house artists. The designers were Pyotr Lambin (Act I), Konstantin Ivanov (act II scene 1 and act III), Heinrich Levogt (the Underground Chambers), and Vassily Perminov (Act III, scene 2, together with Ivanov). Perminov and Levogt had shared Samson and Delilah that season together with the veteran Matvey Shishkov; known for Sleeping Beauty and La Bayadere. Levogt painted the Ball Act for Swan Lake, and Ivanov's castle terrace with turret is a sister design to his courtyard for Raymonda's 2nd act.

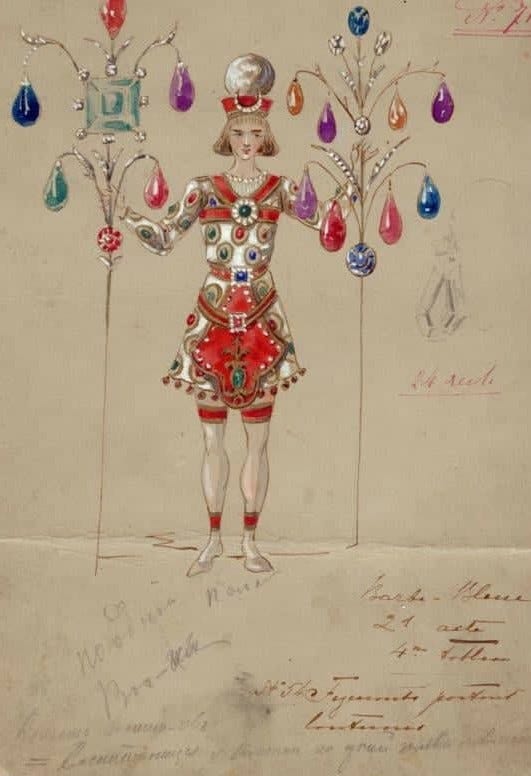

The costumes are by Ivan Vsevolozhsky. The director refrained from taking credit here, but it is proved by known drawings and a report (30 Jul 1896), wherein he informs Petipa to be busy finishing them. The designs place Bluebeard from the late 17th century into the 18th, with the last act, and some playful lunges forward. Looking at the 3rd act designs; the thought occurs they were of influence to Alexander Benois for Le Pavillon d'Armide (1907).

Music

While Bluebeard took the stage, the infinitely more famous Raymonda was in preparation. The music was by one Alexander Glazunov. Bluebeard's music was by one Pyotr Schenk. Who you say? Pyotr Schenk. Unknown, unloved, frowned upon and dismissed. One should make a case here for Schenk’s restoration/promotion to the ‘class of symphonists,’ for there is every reason to believe the management put Schenk on a par with such composers. And why shouldn’t they? He went from child prodigy to a respected composer/conductor/pianist/critic. Schenk's Andante, a symphonic work, was called a ‘brilliant debut’ in 1890 (Yanina Gurova).

Pyotr Petrovich Schenk (1870-1915) graduated from the St Petersburg Conservatory as a pianist in 1887. He took up music theory later. As a 6-year-old orphan, he was adopted by Mariinsky employee Pyotr (Mikhailovich) Schenk and his wife, the actress Ekaterina Reinecke - so a good part of his youth played out in and around the theatre, where he began as an official to have a steady income. He should have drawn attention to himself there prior to his ‘brilliant debut.’ Following this success, Schenk appeared in the concert hall as a conductor and pianist, performing his own works and that of others. So, if the imperial ballet bargained for a ‘symphonist,’ they had one in Schenk. According to unverified sources, Schenk started on Bluebeard already in 1892. This discords with Pashkova’s timeline. If the management discovered Schenk after Tchaikovsky’s demise (1893), they surely eyed him as a candidate to follow in his footsteps. Some years after Bluebeard and Salanga (a joint composition with Klenovsky, eventually produced for the Theatre School), director Vladimir Teliakovsky commissioned no less than five operas from Schenk (1904-1914). The passive stance of viewing him as ‘a mere 19th-century-style ballet composer’ is made easy because neither his operas, nor his non-theatrical output - comprising symphonic, vocal and piano works - hardly survive in performance.3 The fact that Bluebeard tended towards contemporary can be drawn from reviews like this: ‘… It is not dansante. Ballet needs melody, clear rhythm […] which Schenk disregarded ...’ (Konstantin Skalkovsky).

Mikhail Ivanov was the composer of La Vestale, and as such versed in working with dance. His reaction was spot on: ‘… Complaints about the non-dansante quality of Mr Schenk’s music have been heard before in connection with ballet music that went on to produce unquestionable delight, such as Sleeping Beauty ...’ Chronicle had a comparable view: ‘… Schenk cares about the qualities of his melodies. Some are genuinely beautiful […], far removed from commonplaces […], naturally, in ballet music one cannot entirely avoid trivialities, but any serious composer can console himself knowing that Tchaikovsky, Glazunov, Delibes and Lalo all have been there …’ (1899).

And indeed, non-ballet spheres were much kinder. Schenk’s opuses ‘… are of a lyricism and tenderness of intonation and have a beautiful, bright melodic style […], a special […] sophistication that sets them apart […]. He never writes music for its own sake, always trying to imbue it with spiritual depth […] and imagery of content …’ (Niva. No. 41, 1913). In 1898, Schenk had started a family. His appointment of Head of Repertoire and the Music Library (1900) should be in conjunction with that.

Pierina Legnani

Petipa created Ysaure for the prima ballerina Pierina Legnani, whose contract with the Imperial Ballet ran from 1893 to 1901. It was the first full-length role Petipa did for her. The Italian star had just scored triumphs in Swan Lake and the often-billed Hump-backed Horse. Ekaterina Geltser, soon-to-be understudy for Raymonda, asserted that Legnani was best served by a light plot and lots of technical tour de forces - meaning she was no great actress (Slonimsky). But what about Bluebeard's lengthy Scene Mimique (the dramatic terrace scene with the key and impending death)? The critic Alexander Plescheyev did not think much of it, but then there is the strong character Medora from Le Corsaire, and the not un-intense drama of Odette. It is worth remembering that the biased Geltser aspired to be a ballerina (either in the capital or Moscow). Her observation should also be seen in context of Stanislavsky's ideas, which Geltser developed after her involvement in acting. Alexander Shiryaev was ambiguous about the matter: ‘… Many accused Legnani of insufficiently advanced mime, but I cannot agree there, she fully captured her roles, skilfully expressing all thematic situations. Her problem lay in her being a blonde with delicate, inexpressive features. Understanding her acting meant one had to see her face, and that was impossible at great distance from the stage …’ Studio photos with an expressive-eyed Legnani give about the distance of the first stalls rows, evidencing how patrons there would have experienced her. Apparently, contradictions originate in seat position and opera glasses – audiences further form the stage without them would help cement Geltser’s opinion.

Legnani's technique though, was beyond dispute. After her 32 fouettés in Cinderella and Swan Lake, Legnani performed another novelty in Bluebeard: triple pirouettes in the Pas de Deux Electrique. An educated guess: these were triple pique tours en dedans, executed twice on her variation’s last bars, where they precisely correspond to the percussion (going by the 2014 orchestration). ‘… ballet-wise, equal to discovering America for a second time […] she would be needing a surgeon, is she to continue this way …’ said Plescheyev, no stranger to hyperboles.

During the run-up to Bluebeard's premiere, Petipa gave an interview. He had a go at ballet abroad (from Russia), using the word ‘tomfoolery,’ blaming the Italian School for ruining the art form, and calling Luigi Manzotti’s Excelsior a féerie rather than a ballet.

But Italian or not, Legnani was in the zone. Plescheyev observed how her virtuoso steps were done ‘in the understated manner characteristic of her.’ This explains why Petipa loved working with Legnani, as he had trouble with virtuosity for its own sake. Legnani had four variations in Bluebeard: one in the grand pas d’action, two in the underground chambers (the Hannami or Variation Orientale and Variation diamantée) and the fourth in Electrique. From Petipa’s notes on the Variation orientale: ‘… the Japanese surround her in a flash, and place their fans on the floor for her to tiptoe over them …’ (the joyful adagio and atmospheric variation were followed by a stormy coda). Ultimately, Legnani was to move up to five in Raymonda.

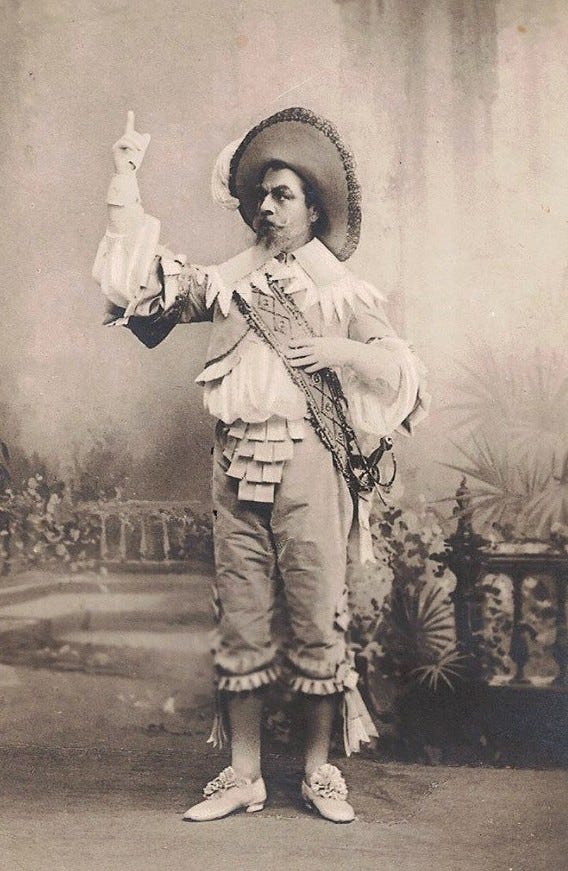

Bluebeard’s Male Dancers

With Bluebeard's title role, Pavel Gerdt set out on a long-delayed leave of his days as jeune premier. Although he was still to create another ‘son role,’ Ioritomo in The Mikado's Daughter (1897), and return to the heroes of Pharaoh's Daughter, Esmeralda and La Bayadere, his transition to character parts had definitely arrived. Abderakhman in Raymonda became his number one in this constellation.

The talented Sergei Legat danced Arthur. He was picked at an unprecedented 21 years of age for a full-length ballet, after sampling leading roles in shorter works. Legat would rise to the rank of principal dancer. However, in the Pas de Deux Electrique, Legnani was not partnered by Legat, but by Georgy Kyaksht, the company’s Cecchètti-adept. He was often called to perform virtuoso work by nameless characters, and in Bluebeard, his variation stood out for intricate petite allegro (Petersburg Gazette). The culture of the leading man going all the way to the grand pas de deux was by no means in place in the late 19th century. Legat, dancing classical in the grand pas d’action, was technically accomplished enough to do Electrique himself - records attest to that. So, was it done to let Kyaksht have his share in Petipa's jubilee - or did the directorate cater to Gerdt’s sensibilities? Splitting up the hero role dancing/acting-wise was an old habit to accommodate aging danseurs. In Swan Lake, Gerdt’s variation was danced by Alexander Gorsky, a younger artist wearing a similar costume, as Gerdt himself had done for Ivanov when young (today, we smile wryly on this one, but it is akin to film stars passing on their own stunt work, a cultural practice we take for granted). But to have someone acting and dancing as jeune premier in the first show wherein Gerdt was ‘officially old,’ would pose a change he might have objected to. Chances are that Vsevolozhsky and Petipa treaded lightly here. Legat did lead the last dance, the cotillon, with ‘his bride’ Legnani.

Supporting Cast

A strong supporting cast included Olga Preobrazhenskaya as Anna. Matilda Kschessinskaya, with Aurora, Swanilda and Sugar Plum under her belt on her way, danced Venus. Sergei Legat’s brother Nicolai was Mars, Matilda's brother Iosif Kschessinsky Ebremard. Alexander Oblakov, Swan Lake’s Benno, portrayed Raymond. Ysaure’s friends were Anna Johanson and Klavdia Kulichevskaya, with Geltser as second cast to Johanson. Lastly, Olga Leonova - Diana in The Awakening of Flora - became Curiosity.

The first act featured Anna Noskova, Vera Ivanova, Varvara Rikhlyakova and Vera Mosolova portraying peasant girls, vying for a prize from Bluebeard in the Concours de Danse. The dungeon chambers included Maria Skorsiuk, Shiryaev and Gorsky in l’Argenterie, while Alfred Bekefi and Stanislav Gillert were in the Orientals. Gorsky’s costume has been preserved. The all-female Pas des Joyaux had Maria Tatarinova (Ruby), Tatiana Nikolaeva (Sapphire), Mosolova (Emerald) and Ivanova (Diamond) leading a corps de ballet of 24 plus students.

Premiere

Complications occurred on the eve of the grand happening. Notably, Gerdt injured himself. When Giorgio Saracco, ‘reputedly the best Italian mime’ (Petersburg Gazette), was announced as his replacement, Gerdt’s popularity surfaced: the company men protested against Saracco. Saracco, on good terms with the Mariinsky, had staged Sleeping Beauty that March in Milan, and was a frequent producer for the capital’s non-imperial theatres. After Saracco’s stepping in during some late rehearsals, Gerdt soldiered on through the premiere (8 Dec) and the second performance (15 Dec), Legnani’s benefit. The biggest obstacle for Gerdt, suffering from a pulled tendon in his leg, would be chasing Legnani when she flees after praying. We are to assume Petipa kindly altered this passage. Had Saracco performed, he would have been the first Italian male dancer since Cecchètti on the Mariinsky stage.

Around this time, Maria Petipa stormed out after being told off on her execution of the Polka Fin-de-Siècle. She retaliated in the press: ‘… […] someone came up to me, declaring that I dance the polka with too much abandon, out of tone with the ballet’s approach. This was not my first polka, having performed it […] before the most select public, and no one, absolutely no one has ever reprimanded me in any way. In general, I think I am past the time when any reprimand is to be made, and this person’s intervention seemed utmost offensive …’ (Petersburg Leaflet).

This is interesting. Firstly, if Maria considered herself past direction, she was used to get none by then – imagine the consequences for her Lilac Fairy variation. Secondly, the ‘someone’ Maria refers to cannot have been anybody but her father. His jubilee was quite the thing, and if someone else had offended her, she would not have taken it out on him. Cunning enough to shield his name from the press, she was both cordially in regard to that jubilee and aware of how finger-pointing could backfire on her. Petipa was certainly disappointed when she declined, wishing to have all his girls on stage with him: Nadezhda danced in the Orientals, while his two student daughters, Lubov was surely distributed in the Monaco and jewels, and Vera in the bourree or Valse des Etoiles.4 (Maria was replaced by Ivanova, but did dance Fin-de-Siècle later on). Nevertheless, Maria’s insight may have been apt, the Chronicle called the polka’s music ‘zestful.’

Various descriptions of the festive ceremony survive. After the ballet finished, Petipa was brought on stage, flanked by Legnani and Kschessinskaya, to deafening cheers. Lev Ivanov delivered a short speech and Felix Kschessinsky placed a laurel wreath of gold on his head. Then, adorably, a boy pupil spoke welcoming words, and Petipa kissed the children. Bouquets, flower wreaths and expensive presents piled. There was a silver baton from the orchestra, presented by Leopold Auer, Albert Zabel and Sergei Morosov, a sizeable silver service and ditto dolphin, and a diamond-studded, enamel cigarette case, to name but a few. The gifting was interlaced with words by representatives of various theatres, and ballerinas such as Emma Bessone, Rosita Mauri and Antonietta Dell’ Era had sent telegrams. Most importantly and unprecedented, Petipa was styled Soloist to the Court of His Imperial Majesty. Naturally touched, he uttered thank-yous and was again rewarded by bravos from audience and company alike. The yearbook devoted nine pages to the jubilee artist.

Next day’s reviews for Bluebeard admired its lavishness, and were largely appreciative of Petipa: ‘… The work of Marius Ivanovich - poetical, inexhaustible - produced […] marvellous scenes, astonishing in artistic taste, originality and variety …’ (Petersburg Gazette).

‘… The staging has vivid imagination and taste […], which does not in the least suggest a weakening of creative powers, and if it has some defects, they are not Mr Petipa’s […]’ (Novoe Vremya). Alexandre Benois thought that ‘Bluebeard had witty and charming elements.’ Inevitably, some were less enthusiastic: ‘… a creation not really befitting our exemplary stage …’ (Birzhevye Vedomosti).

The cast received great compliments. ‘… Mr Gerdt delivered his role brilliantly, even though he is still limping …’ (Petersburg Gazette). Benois and his circle were amazed by Gerdt’s dramatic interpretation, and he underwrote the mirror dance, ‘in which Legnani’s double was that original and charming dancer Kulichevskaya.’5 Preobrazhenskaya was acclaimed for her first big acting part and flawless variation, Kyaksht was called to repeat his, and Legat won approval after the second show.

Two commanding newspapers were positive about the sets: ‘… of the decorations, beautifully drawn is the garden in front of the castle […]’ (Petersburg Gazette). ‘… The decorations are sumptuous, but Mr Lambin’s garden and the ‘Temple of Saturn,’ by Mr Ivanov and Mr Perminov, should be considered the best …’(Novoe Vremya).

Ysaure’s 2nd act costume elicited scorn (Petersburg Gazette) for being something of an underskirt, worn in the presence of a knight and then for the cold and damp subterranean vaults. Plescheyev was cautious about the mime scenes – opining that even Zucchi would be unable to do something with them - and the Underground Divertissement. He doted on Kschessinskaya: ‘… [her] dancing […] is artistic, with an astonishing purity […]. It bubbles like champagne, enthralling the public …’ and Legnani, who ‘traversed 15 versts on pointe during the performance.’

On 20 December, Petipa celebrated with the company in the VIP restaurant of the French court chef Pierre Cubat. The evening was organised by Plescheyev and Bezobrazov. Skalkovsky kicked off with a speech in French. Among the many invited dancers was Maria, indicating that the friction with her father was smoothed over. The string orchestra of the Preobrazhensky Regiment played a march, and a happy Petipa danced the mazurka himself.

Reflections

Bluebeard’s ouverture foreshadowed some of the anguish that was to culminate in the Scene Mimique. The love scene was accompanied by solo violin. There were numerous appealing dances and scenes; ‘fresh, vivacious, merry…’ (Chronicle) . The grand pas d'action (Act I) may have echoed operatic multiple voice airs, like the sextet from Lucia di Lammermoor, ‘Adieux! Je ne veux pas te suivre’ from Tales of Hoffmann or anything Rossini, accommodating varying emotions: Bluebeard being in, Ysaure wanting out, Arthur wanting in, Anna and friends merrily on, the brothers marrying off. At one point, the four ladies were supported in synchronised promenades (ten to one en attitude) by the gentlemen. Plescheyev ascribed a whirlwind quality to them, something rarely seen nowadays. Schenk introduced an organ solo for the off-stage wedding. Presumably, this offered Sergei Legat, alone on stage, a dramatic build-up. Some of Petipa’s notes also lift a bit of the veil, proving that the act ended poignantly: ‘… […] the march at the end, when they are married – it takes place only at the back ...’ Deductively, musicians stood behind the gate, or the corps de ballet passed by, while Arthur stood centre stage with his flower.

The next noteworthy moments were in Ysaure’s bedroom (Act II, scene 1). The photo of Legnani and her posse in front of the mirror is a familiar one. The trick of Kulichevskaya as Ysaure's image (behind a transparent gauze) was later made use of by John Cranko for Onegin. In turn, Petipa referenced his own Camargo, borrowed from Perrot’s Éoline or his father’s Farfarella, and they were probably not the first to do it either. Because Kulichevskaya was one of Ysaure's friends, imitating Ysaure can have been a reaction game. Arthur played the lute to a canzonetta, and similar to Raymonda, his string plucking was accompanied by the harp. It evolved into a passepied with Anna, which suggests she cheered him up. Chronicle thought the musical evolvement here quite unusual. There is a studio photo of a scared Legnani, tombée in Gerdt’s right arm, weakly holding him off, while he gestures threateningly to Arthur. This pose credibly pertains to Bluebeard’s declaring to consummate the marriage soon, and Arthur, though in no position to do so, protesting meekly.

Ysaure’s bedchamber and the dungeon scenes were connected by a musical panorama, but unlike Sleeping Beauty, the moving underground was ‘decidedly depressing for an audience, to the accompaniment of Mr Schenk’s monotonous music …’ (Petersburg Gazette). Chronicle disagreed, speaking of a ‘melodic flow.’ Whatever happened, the outcome cannot be defended, but the idea can: given the setting and denouement of Ysaure’s adventure, a hopeful panorama would be a mistake. Besides, after Beauty, Petipa’s artistic curiosity may have led him to do a negative one – a journey over the Styx sans boat, as it were. The bedchamber set was hung halfway the stage, and when flown out would reveal the moving ‘wands.’ Afterwards, Ysaure and Curiosity entered front stage, and to show their going from room to room, use was made of a false proscenium, behind which stage hands could hastily prepare each subsequent set.

Petipa created a cinematic effect avant la lettre with the horror room, and took dancing objects to the next level. The kitchen utensils of l'Argenterie remind one of the animated Beauty and the Beast: the Disney Studios do not just owe 1930s musicals.6 Petipa referenced himself too, think of Le Papillon (1874) with dancing vegetables and The Magic Pills (1886) with dancing games.

As for the horror scene, audiences were readied for the hanged wives via the playbill, but no doubt, Petipa ensured a good scare with a brilliant coup de théatre nonetheless. Pashkova built it up aptly: Ysaure fits the key with trembling hands, then the two halves of the door open slowly. First, there is nothing but an ominous darkness. Ysaure steps into the dungeon, takes a candle from the wall, manages to light it, and then, when holding it up, the theatre lights must have taken over, and … well, in that moment, the audience became Ysaure.

These effects were decisive factors in making Bluebeard a love-or-hate-it ballet. Nicolai Legat counted among its supporters, while Tamara Karsavina, departing from the reserved manner typical of ballerinas, called Bluebeard shameless. She devoted half a page to its absurdities, citing Gautier - the long-dead librettist who had no time for divertissements – to back up her go at Petipa’s revue- and pantomime-like solutions, being derisive about both cutlery and corpses.

Incidentally, while mocking the horror scene, Karsavina left a detailed description of it: ‘… and then she discerned six bodies (thinking about it, extremely well-preserved). They still dangled on ropes, their white dresses unstained excerpt for blood trails […].’ The ‘fresh’ state of the bodies was, of course, magically induced – something Tamara Platonovna, in the business of fairy tale, should not have been cynical about.

Critique about Petipa’s cross-over from high-brow culture to popular art was seized on by the 20th century; east of the Iron Curtain for upper class decadence, and west, for not matching the aesthetics ballet came to represent. But was dancing cutlery really that far removed from dancers tripping over the stage costumed as skyscrapers? Think here of Massine's Parade, doted on by art history teachers for its modernity and innovation. What if Petipa had come up with it, to Minkus instead of Satie’s music? Cross-overs in ballet keep coming back, today it is a way to make the art form more accessible. A global hit is Christopher Wheeldon’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (2011), complete with dancers as playing cards, flamingos and hedgehogs. Pig corpses - rather than female ones - dangling from the ceiling.

A closer examination of the Imperial Yearbook sheds light on an intriguing matter: Ysaure's relationship with Curiosity. Curiosity manifests when Ysaure is drawn to the iron key. In French and English, she is described as ‘The Spirit of Curiosity ...’ taking cue from the piano score. But it is a passive mistake to place the long-robed Curiosity in the same category as the Lilac Fairy, Raymonda's White Lady and Cinderella’s Snow Flake Fairy (Fairy Godmother). Here is why: the Lilac Fairy is so much in control of the narrative that she is little short of writing it herself, Fairy Godmother makes wishes come true and the White Lady, Protectress of the House of Doris, is very much in ‘protectress mode,’ influencing the outcome of the duel. Curiosity is far from these active characters. Accurately described as an allegory (Chronicle 1899), she is but an idea, a figment; popularly attached to female energy since Pandora’s urge to open the box. Ysaure herself thinks things first, she decides to open the doors to the dungeons and various chambers. Curiosity merely represents her initiatives, she is a physical manifestation of Ysaure’s will: when Karsavina wrote ‘Curiosity, a symbolic figure, egged Ysaure on in front of the proscenium,’ the patrons saw a metaphorical ‘will I, won’t I.’ Yearbook and libretto don’t name her ‘spirit’ or ‘fairy,’ for in ballet, these are entities that act with autonomy. On the doorstep of psychology, Ysaure and Curiosity’s relationship appears crafted with insight in the human psyche.

In Act III, Schenk’s festive polonaise was inspired by Chopin. There are the three aspects of Time: Past, represented by an earthy character dancer (Alexei Bulgakov), Present, personified by a young dancer (Fyodor Vasiliev), and a small pupil (Sofia Liudogovskaya) posed as Future. Dissimilar to Curiosity, the Imperial Yearbook describes them as spirits, for, in accordance with the Russian perception of fate, they actively shape life. Each of them appeared from a different temple door.

Surmising, the Pas de Deux Electrique was inspired by the freshly invented way of lighting. Earlier that year, the Kremlin was decorated with thousands of electric light bulbs for Nicholas II’s coronation. The unprecedented feat awed the world - and Petipa and Vsevolozhsky, present in Moscow for The Pearl. Lastly, there is Saturn. As a symbol, Saturn is associated with hard work, continuity, organisation rule and the wisdom of old age - all applicable to the force that Petipa was. Chances are that Pashkova submitted the libretto before Bluebeard was chosen for Petipa's jubilee. So, both electricity and Saturn sound like later proposals; Saturn by Vsevolozhsky to honour his long-time friend with the allegory.

In its initial season, Bluebeard was billed no less than 13 times. After a two-season hiatus, the ballet returned on 3 September 1900, with Preobrazhenskaya as Ysaure. The role ensured her promotion to ballerina, right on stage between the 2nd and 3rd act. Some thought that Ysaure ‘did not accord with her gifts’ (Novoe Obschestva), but Valerian Svetlov disagreed: ‘… gay and vivacious, with perfect technique and a supple grace […], her mime was best with Curiosity, [her sadness at her] separation from Bluebeard [this shows that he was not the single faking person, P.K.] and her liberation, all portrayed with much integrity and authentic feeling …’

This Bluebeard was also the last performance of Petipa’s talented daughter Lubov, who hastily left the company after just one season, preferring a domestic life. Pavlova became the new Anna/Venus. Teliakovsky scoffed. He compared Bluebeard favourably to Camargo sheerly because ‘boredom reigned less.’ Through the years, Bluebeard pops up in his diaries: ‘The performance was sluggish, and at the end the dancers even bumped into each other. Preobrazhenskaya’s mime was very weak. It’s not a strong production in all respects […]’ (11 Nov 1901).

On 19 Oct 1903, Bluebeard ‘old-style’ received its final performance. Six days prior to that, the casting commission met. It was a body installed by Teliakovsky to call a halt to Petipa’s alleged bribe-taking and role owning. Petipa tried, initially outside the agenda, to arrange that Olga Chumakova be replaced by his daughter Vera.7 As casting used to be Petipa’s prerogative, it was humiliating for him, but this particular action does reek of nepotism. Teliakovsky did not condone it, and neither did member Preobrazhenskaya, to whom Petipa turned for help - an embarrassing situation for Preo. Petipa, sour, then went to the theatre to conduct the rehearsals with orchestra of Cavalry Halt and Giselle, taking over from a sick Shiryaev. The next day he resigned from the commission and announced to stop rehearsing ‘old ballets.’ Bluebeard’s daily rehearsals now fell to Nicolai Sergeyev and ‘that mean-spirited Gerdt’ (Petipa). Aside from Preobrazhenskaya and Pavlova, the friends were Lubov Egorova and Vera Trefilova. Because Kyaksht guested in Moscow, Sergei Legat performed Electrique in addition to Arthur. For once Bluebeard had a full hero role 20th-century style. In his diary, Teliakovsky criticised the quality of the Scene Mimique, but added that the theatre was packed and the performance well-received.

With delegating the Bluebeard rehearsals, Petipa forewent the last possible involvement to be had. When listing Bluebeard in his memoirs, he misplaced the ballet on the timeline. ‘1899: La Barbe bleue. Musique de Mr Schenk. Programme de Mme. Paschkoff, montée par Mr. Petipa. Exécutée par Mlles. Légnagni, Préobrajenskaïa et Pawlowa II [sic], grand succès.’

Nicolai Legat’s Bluebeard

In 1910, when Legat restaged Bluebeard, the ballet world had changed. The company had lost a principal dancer when Nicolai’s brother Sergei, the original Arthur, committed suicide in 1905. A month on, Nicolai landed the coveted position of 2nd Ballet Master - circumstances were far from ideal. When Petipa died that summer, Nicolai moved on to 1st Ballet Master. Fokine, on the rise as choreographer to Legat’s chagrin, became 2nd Ballet Master. Together with the majority of their colleagues, Fokine had conquered Paris with the Ballets Russes. Legat, though in a powerful position, was no diplomat and moreover, had trouble finding his voice as choreographer: framing his admirable command of the classical technique with dramatic context was not his strong suit. His ballets Puss in Boots (1906) and The Little Scarlet Flower (1907) flopped.

So, Legat also staged Petipa. After The Seasons (1907) and The Talisman (1909), he revived Bluebeard. Reportedly, use was made of the old production, bar fresh dresses for Kschessinskaya, ‘who had herself redesigned’ by Prince Alexander Schervashidze. Legat’s Bluebeard was presented on Gerdt’s benefit, that other defender of the ‘old ways.’ Beside Pavel Andreyevich were Kschessinskaya as Ysaure and Samuil Andrianov as Arthur. Legat had always sung Petipa’s praise, so how much did he actually change?

Teliakovsky: ‘… I attended the dress rehearsal of Bluebeard. The ballet was resumed as it had been performed in the past. It’s really sickening to watch ...’ (10 Dec 1910).

The italics tell that Legat’s lay-out was very similar to Petipa. However, since Teliakovsky’s knowledge of steps was limited, his remark does not clue us in on alterations there. Slonimsky suggested that Legat made ‘small adjustments’ in The Seasons and, in relation to The Talisman, Krasovskaya claimed that ‘Legat frequently cited Petipa’s choreography’ (she gave no source). Seeing that these ballets preceded Bluebeard, Legat’s modus operandi should have stayed close. Another motivation to do so was to honour the deceased Petipa, and artists who had danced in the old Bluebeard were still plentiful. To a fair degree, Petipa could be ‘knit together again.’

Teliakovsky continued: ‘… there are costumes with pots, dishes, forks […], this is some kind of circus, not a ballet ...’ The comment is peculiar. The kitchen utensils had been a thorn in the director’s side since Petipa’s days, and his sneering only makes sense if he had asked Legat to get rid of them. He went on: ‘… The music is quite satisfactory, Kschessinskaya dances, and spunkily at that. I forbade Karsavina to go up the staircase, for I consider it too risky …’

Remember the injured Gerdt, unable to give chase to Ysaure? Presumably, Ysaure’s running up to the turret was never reinstated, neither by Petipa nor Legat, otherwise Teliakovsky would have forbidden both sisters to go up. Apart from the poorly maintained staircase, Teliakovsky confirms the ‘modernity’ of the music. He abhorred the scores of the old-style, ‘non-symphonic’ ballets. The following review indicates that tastes in ballet music were changing: ‘… After […] Tchaikovsky and Glazunov, Bluebeard’s cleverly composed score is among the best that Russian ballet has to offer. One can easily and comfortably dance to it […] the music’s great merit is that it flows richly and freely without stopping incessantly, variations are woven into it. A good example of this is l'Argenterie […]. The ballet was a big hit …’ (Chronicle, 1910 No 51-52).

Gerdt was applauded in the same review, but the rest of the press was ‘polite, if restrained’ (John Gregory); mentioned were Legat’s good taste, interesting groups and individual dances. Bluebeard was cancelled after Gerdt’s benefit. Legat had nothing to gain by this, meaning it was at Teliakovsky’s instigation. By a stroke of luck, the ballet came to be programmed once more, almost a decade on. But by then, Legat, Teliakovsky, Kschessinskaya and Gerdt were all gone.

Post-Revolution

When Bluebeard was next seen, in 1918, it was not just the ballet world that had changed. War and revolution had broken out, and while the Bolsheviks pulled Russia out of WWI, they plunged her right into the Civil War. Legat botched up a possible come-back after an over-extended leave. Gerdt had died, and Kschessinskaya was running from the Bolsheviks. Teliakovsky was forced out of his directorship weeks into the revolution, and that is how Bluebeard could come back.

Alexander Monakhov and Alexander Chekrygin oversaw the production, billed for Ivan Kusov’s benefit. Kusov, who had risen from l’Argenterie through Raymond to Bluebeard, inherited the title role from Gerdt. He must have had love for Bluebeard, and influence, for reviving it was not without its hurdles, let alone obtaining a benefit in this uncertain period.8 Elena Smirnova danced Ysaure, Elizaveta Gerdt Anna, and the upcoming Olga Spessivtseva one of Ysaure’s friends. Pierre Vladimirov danced Arthur. ‘Our own Clark Gable,’ sighed Alexandra Danilova. As good-looking as the original Arthur, the lamented Sergei Legat, this ‘Gable’ was no less incorrigible without Kschessinskaya having his back. One dancer reprised the role he created 22 years ago: Iosif Kschessinsky, who returned to Ebremard. According to the critic Denis Leshkov, Chekrygin made extensive cuts that rendered the ballet nonsensical. Presumably, there was no one to restrain him during the power vacuum.9

Bluebeard’s fate was decided in a meeting of the powers that be in the spring of 1919. This happened during the short tenure of dancer Boris Romanov as ballet master, who was ‘even elected to be director’ (Souritz). Along with Bluebeard, The Awakening of Flora, Paquita, Enchanted Forest, Les Caprices du Papillon, The Magic Flute, Graziella and Cavalry Halt were sacrificed on the, er, non-altar of Soviet ideology. What springs to mind is that these were all ‘happy ballets’ – read court pleasers. Europe, under dark clouds, had no longer patience to maintain and produce art for pleasure, satire now being the best bet for fun. ‘Art serves understanding, not entertainment,’ said the German painter Max Beckmann, representing the mindset of the interbellum.

But the factors behind cancelling Bluebeard likely differed from the other works on the list. Bluebeard stands out as the single fairy tale. So, what about the triumph of good over evil, eagerly propagandised with Sleeping Beauty and not that different in Bluebeard? Had the new ballet culture not by and large validated the music? Benois, who was in Petrograd in 1918, thought otherwise: ‘Chief reason [to cancel] was the music, which may not have been inferior to Minkus and Pugni’s, but seemed banal and colourless to the public who had learned to appreciate and love Tchaikovsky.’ But Benois wrote this on the brink of WWII, and had not heard Bluebeard for over two decades, if not longer. It can have coloured his memory.

Supposedly, it was a question of composer, not composition. Schenk had died at 45, in the midst of WWI. The Bolsheviks blacklisted his name, and chances are that his close collaboration (on romances) with the Grand Duke Konstantin (K.R.), a cousin of Nicholas II, was the cause. His family was harassed, and his opuses came to be neglected. There may have been something quotidian at play too with Bluebeard: the state of the production. After Teliakovsky shut it down following Gerdt’s benefit, the sets were stored and credibly in a worse state of neglect: if safety regulations prevented Karsavina to go up the turret in 1910, ten to one it was not safer in 1918, leading Elizaveta Gerdt, Anna, to look out for her brothers from a less lofty vantage point – an ineffective one. If so, did Leshkov blame Chekrygin and Monakhov for such matters as well?

A snippet: did the Pas des Joyaux play through the mind of George Balanchine while creating Jewels (1967)? Observing the timeline, Balanchivadze may have danced in Bluebeard’s dance for pre-graduates, the monaco, like Mikhail Fokine.10 A Van Cleef and Arpels visit allegedly inspired him to do Jewels, but not even a one-off (the 1918 Bluebeard) should have escaped his phenomenal memory. And let’s face it, Van Cleef and Arpels is a sexy selling point, a forgotten oldie isn’t.

During the 1930s, the Kirov revived a selection of Petipa’s classics, but Bluebeard was not among them. Agrippina Vaganova, then at the helm of the ballet, had graduated a year after its premiere. Bluebeard is not mentioned in her biography, leading one to assume she had no love for it (she was known to ridicule Cinderella), reserving her pruning for other ballets.11 As it appears, not a single titbit of Bluebeard found its way into another work; a common practice at the time. This only changed in the 21st century, when Yuri Burlaka inserted a portion of the music in his Esmeralda (Bolshoi Ballet, 2009), before Vassily Medvedev interpreted the Pas d' Electrique for Dance Open in 2014.

Postscript

Unlike many other ballets of the period, Bluebeard was not notated. The ballet is lost, it can no longer defend itself. This leaves us deprived of a chance to form our own opinion and vulnerable to parrot the naysayers of the day. These were mostly people who endorsed innovation - a concept we are expected to applaud indiscriminately.

So how can we cease to view Bluebeard as an expendable to pass by hurriedly, in the correct race from Tchaikovsky to the Ballets Russes? Slowly, more material resurfaces. It will not be enough to restore the ballet, but it should be enough to restore its reputation, readying it to be recognised as a worthy step between Swan Lake and Raymonda. And above all, accepting Petipa’s chosen modus operandi as a concept, the same way we grant other great artists. Enjoying, contemplating, studying, asking questions, but never dismissing it because a template of the art form as it developed does not fit.

“… I was bursting with gratitude, and on leaving the Director, gave thanks to heaven, which had sent me such good fortune … I want to stay here for the rest of my life …”

And so, back to Petipa’s memoirs and his prophetic words. In the five decades that were to follow that subsidised summer, he brought his audiences sylphs, nereids, naiads, stars, temple dancers and whatnot. We are over-familiar with them, so a walk with Curiosity to Petipa’s corpses and cutlery would befit any completist.

© Peter Koppers

Notes

1) The quotes are an amalgam of Petipa’s memoirs and what he told the Petersburg Gazette on the occasion of his jubilee and Bluebeard’s premiere. There are contradictions.

2) Going by the ordinary key-size on surviving photographs, the blood must have been hard to discern for everyone not sitting in the front row stalls.

3) To be precise, Schenk composed 11 stage works: aside from the 2 ballets and 5 operas there were 2 operettas and 2 plays. Some published music is still available.

4) Since the Imperial Yearbook doesn't list student names for the dances, this remains an assumption.

5) In his book Reminisces of the Russian Ballet, Alexandre Benois erroneously places the Mirror Scene in Cinderella.

6) Going Disney, even closer on the timeline to Bluebeard than Beauty and the Beast were Sleeping Beauty (1959) and The Sword in the Stone (1963), both with come-alive kitchen utensils. The idea to animate objects should not be too far-fetched for Disney’s animators in itself, but one can never rule out the possibility of them meeting refugees or travellers who had actually seen Bluebeard.

7) The tenability of the committee’s ‘democratic process’ is doubtful, since all members had friends, family and lovers in the company they wished to promote.

8) Benefit performances were tied to an elitist culture and stopped after 1919. Afterwards, there were some to collect money for groups, like theatre workers (Belenky).

9) A month after Bluebeard, dancer Leonid Leontiev, in his capacity as chairman of the ballet committee, had an interview with Biriuch Petrogradskikh Gosudarstvennikh Theatrov (16-22 Dec. 1918, no.7). He admitted that the company was without a ballet master with Fokine abroad.

10) The website of the George Balanchine Foundation does not list Balanchivadze’s partaking in Bluebeard. But while extensively researched, Russian information about this particular period and performance remains scant and may still surface.

11) The ballets Vaganova reset are Le Corsaire (1931), La Bayadere, Giselle (both 1932), Swan Lake (1933), Esmeralda (1935) and Paquita's Grand Pas.

Sources & Bibliography

Sergey Belenky

Andrew Foster

Doug Fullington

Robert Greskovic

Amy Growcott

Sergey Konaev

Roland John Wiley

Alma Mater, Yanina Gurova

Dancing in Petersburg, The Memoirs of Kschessinska, Translated by Arnold Haskell

Diaries, Vladimir Teliakovsky

The Emperor’s Ballet Master, Nadine Meisner

Era of the Russian Ballet, Natalia Roslavleva

Five Ballets from Paris and St. Petersburg, Doug Fullington and Marian Smith

Fund Guide on Manuscripts and Documents (Putevoditel' po fondu "Rukapi i Dokumentii), St Petersburg Theatre Museum, T Vlasova, etc.

Государственная публичная историческая библиотека.

Imperial Theatre Yearbooks

Kompozitor Pyotr Pavlovich Schenk, Material’i I Biografi, Yanina Gurova

The Legat Saga, John Gregory

Marius Petipa, Meister des klassischen Balletts (Petipa Materials), Eberhard Rebling:

Leader of the Russian Ballet, Nicolai Soliannikov

Observations about Petipa, Tamara Karsavina

Operascribe

Raymonda, Yuri Slonimsky

Memoirs, Marius Petipa

Nash Balet, Alexander Plescheyev

O Balete, Anna Grutsinova

Materials for the History of Russian Ballet vol. II, Mikhail Borisoglebsky

My Reminiscences, Prince Serge Wolkonsky

“Raymonda” and Ballet Herstory: […] A “Raymonda” questionnaire, Alastair Macaulay

Reminisces of the Russian Ballet, Alexandre Benois

Russian Ballet Theatre at the Beginning of the 20th Century (Russkii Baletnyi Teatre Nachala XX Veka), Vera Krasovskaya

Sixty Years in Ballet (Shest'desyat let v balete), Fyodor Lopukhov

Soviet Choreographers in the 1920s, Elizabeth Souritz

The Greatest Russian Dancers, Gennady Smakov

The Petersburg Ballet, Alexander Shiryaev

The State Theatre Library Museum of St Petersburg

The Story of the Russian School, Nicolai Legat

Vaganova, A Dance Journey from St Petersburg to Leningrad, Vera Krasovskaya

Photo Credits

A.A. Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum, Artchive, Bolshoi Archive, St Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music / Санкт-Петербургского государственного музея театрального и музыкального искусства, St Petersburg State Theatre Library / Санкт-Петербургская государственная театральная библиотека, Mariinsky Theatre Archive, Peter Koppers Photo Archive, Salvador Sasot Sellart