(All Russian pre-1918 Dates are given Old Style)

Introduction

In the January cold of 1892, St Petersburg witnessed the return of ballet’s ultimate wood sprite: La Sylphide. The northern capital enjoyed Antoine Titus’s Russian production in 1835, starring Luisa Croisette (and Laura Peysard). The original Sylphide, Marie Taglioni, had danced the role at the Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre in 1837.1 After many commendable sylphs, La Sylphide was largely given incompletely by the 1850s, safe for an 1854 upswing. Tatiana Nevakhovich (Smirnova) danced some Act I performances after having it for her benefit (1848), Marius Petipa chose it as part of his 1857 benefit and a year on, Nadezhda Bogdanova in hers (Act II). The capital’s imperial stages rarely saw the ballet after that, so most patrons with recollections fell into the senior citizen category. There was, however, a ticket holder at the other end of the age line: Tamara Karsavina. The future ballerina, merely 5 or 6 years old (depending on the performance she saw), was utterly inspired by the elusive sylphide, performed by one Varvara Nikitina. It is tempting to think that Karsavina was not the only talented girl in the vicinity. Did a first-year theatre school student named Anna Pavlova manage to sneak into the gods to watch too? Or did Karsavina unknowingly saw Pavlova on stage as well, somewhere behind Nikitina? For, along with her classmates, Pavlova could have been among the farm folk, or one of the tiny sylphides herself. If so, Pavlova should have observed Nikitina’s airy jumps from nearby. Did she take her cue from her, pairing her impressions to her own allegro abilities? And indeed, the critic Konstantin Skalkovsky wrote in Novoe Vremya: ‘... The distinctive features of this ballerina [Nikitina] are unusual lightness of movement, notable ballon, and precision in execution of the classical pas ...’

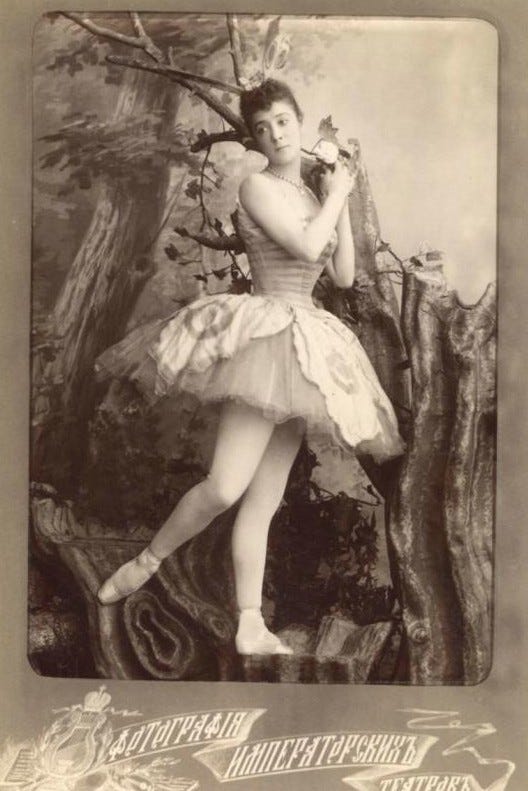

Skalkovsky was Nikitina’s close friend and so not bias-free, but there were other pens dipped in praise as well. His description not just acknowledged talent, but training too. One of Nikitina’s teachers, the revered Christian Johanson, told Nicolai Legat that “... The Russian School is the French School, only the French have forgotten it ...” Nikitina appears to have been its embodiment. Looking at photos of ‘Varya,’ we see a ballerina of the 20th century’s preferred body type, her thinness being a topic of discussion in the 1880s (Khudekov). Nikitina was the Pavlova before Pavlova, with a slightly elongated face and dark, doe-like eyes – except they never oozed comfort around cameras, unlike Anna Matveyevna’s. Who was Varvara Alexandrovna Nikitina, that ethereal, enigmatic sylph?

Nikitina and Skalkovsky

Some 30 letters written by Nikitina herself answer that question. In them, a picture emerges of an exceptionally bright young woman. The historian Maria Ryleeva asserts that the letters were retrieved from the manuscript department of the Pushkin House and the Theatre Library. Most of them pertain to a correspondence with Skalkovsky, an exchange spanning 20 years. The decorated, upper-class dandy and world traveller Konstantin Apollonovich Skalkovsky (1843-1906) trained and worked as a mining engineer, but transformed himself into a writer, a colourful and influential journalist who covered many subjects as serialised stories. Then he experienced a life-changing moment, when approached by a young and attractive brunette.

“[Konstantin Apollonovich], how dare you suggest that when I left the Theatre School, I stopped working?” The bold, reproachful question was put to him by Nikitina.

“I am sorry, it won’t happen again,” answered Skalkovsky, somewhat taken aback.

“Do you have any idea how hard it is to dance?” continued Nikitina.

This little scene sees how Nikitina spoke her mind. Though she kept on addressing Skalkovsky formally, a long friendship was to blossom. To Skalkovsky, however, it meant more; he confessed to having reinvented himself as balletomane and dance specialist because of Nikitina, whom he instantly adored. Although he had written about dance earlier on, he now began to immerse himself in the art form, starting with buying himself a copy of Noverre’s authoritative Lettres sur la Danse et sur les Ballets. Skalkovsky’s brother Pavel Apollonovich, another ballet aficionado, was less enthusiastic about Konstantin’s infatuation. In a rather class-conscious manner, he urged him to forget about this ‘stray’ - referring to Nikitina’s background. Skalkovsky ignored it and continued to support her in his reviews. Nikitina herself was romantically involved with the older philanthropist Fyodor Bazilevsky, a tall, big man sporting an ‘Assyrian’ beard, with whom she lived in his two mansions. Bazilevsky’s father Ivan Fyodorovich had amassed an enormous fortune by being not too fussy about what he took on: wineries, fishing, real estate and eventually gold mining. Bazilevsky subscribed to a box in the theatre, and the librettist Sergei Khudekov suggested that he ‘was involved in the progress’ of his love interest,’ and ‘[...] She was indisputably less gifted than the other two artists [Maria Gorshenkova and Anna Johanson] but enjoyed a much more significant success on stage. For this she was largely indebted to a group of influential followers of the ballet [...].’ The reigning ballerina Ekaterina Vazem called Nikitina Bazilevsky’s femme fatale. But the high esteem in which the ballet masters held Nikitina refutes all this, as did the critic Alexander Plescheyev, who acknowledged her for resisting to replace hard work with a bought career - which would have developed faster than Nikitina’s anyway. Did she, over the years, build up the resentment which culminated in a retirement at 36 when she, with her talent, could easily have added another decade to her career? Might that career have developed more advantageous if the high-profile Italian guests had never set foot on Russian soil? It is a question that hangs like a fog around Nikitina’s name. Truth be told, the first decade of her employment hardly saw any foreign ballerinas on Petersburg’s imperial stages at all. The dominant ballerinas were Russian: Ekaterina Vazem and Evgenia Sokolova.

Early Career

Varvara Alexandrovna Nikitina was born in St Petersburg in 1857, and arrived at the Imperial Theatre School through an orphanage where her real name, Varvara Nikitichna Ivanova, came to be changed. She studied with Lev Ivanov, Christian Johanson and Marius Petipa, the influential men of the Imperial Ballet. The dancer/actress Vera Petipa, Petipa’s youngest daughter, recalled how her father spoke about Nikitina as ‘being highly gifted, an extraordinary natural talent.’ Nikitina caught Petipa’s eye from the start, and he looked for possibilities for her to do solo work in the theatre - four years prior to her graduation in 1877. That way, Nikitina danced an interpolated pas in Esmeralda, roles in The Adventures of Peleus, Peaseblossom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and in the open-air gala of The Two Stars. Then there was La Bayadere (1877). Petipa choreographed a number for her and Sofia Petrova in the Idol of Badrinath divertissement. However, the theatre’s tight policies on roles and advancement were probably the reason why Nikitina, despite being something of a baby ballerina, was fated to become something of a late-bloomer. ‘... such a talented artist, who while still in school promised such great hopes, has been kept in the background for ten years [...]’ said Skalkovsky. Skalkovsky was not alone in observing this, his description just happens to be very accurate.

The Imperial Ballet

In the late 1870s and early 1880s, Nikitina’s name started to appear on the bills in solo parts, such as a Wili in Roxana and Autumn in Paquerette. She attracted special attention when performing a variation in Daughter of Snows: ‘… [in] the Dance of the Animated Flowers difficult solos fell to Miss Nikitina, one of our best young dancers [...]’ (Novoe Vremya). Two months afterwards, Nikitina danced Victorine in Petipa’s Frissac the Barber. ‘… The amiable Miss Nikitina received a basket of flowers for a pas de deux with Mr Karsavin 2 …’ (Petersburg Gazette). Nikitina was also no stranger to character dances, which she danced in Mlada and La Fille du Danube. Her early successes earned her a large state apartment.

Nikitina continued with Zoraya (1881), dancing an Houri variation (a promised virgin to faithful Muslims in paradise) and the Panderetta. The Panderetta earned her a same-breath compliment with the established star Lubov Radina, as they brought about a storm of applause. Nikitina originated the Paquita variation now mostly associated with Cupid in Don Quixote, which came with Petipa’s added Grand Pas of 1881. Vazem recalled how she and her colleagues from the solo ranks, Alexandra Shaposchnikova, Anna Johanson and Nikitina, loved doing it.

Nikitina spent the summer preceding the Paquita revival in the Crimea. There she wrote one of her first letters to Skalkovsky, alluding to her access to a certain Grand Duke. In the letter, Nikitina speaks of the visit she paid him in his Oreanda palace. Ryleeva accords that the Romanov in question was Konstantin Nicolaevich, the second son of Nicholas I. By that time, this Grand Duke had been relieved of his duties by his nephew Alexander III. The new Tsar had no love for Konstantin and his liberal policies, exercised in various capacities during his father’s reign.

Alexander III’s coronation took place in March 1883, and part of the festivities included the allegorical ballet Night and Day. Nikitina travelled with the company to Moscow to perform it, dancing the role of a Dove in the ‘Day section.’ Not long after, Bazilevsky stood as godparent at the birth of Ivanov’s daughter Maria. It is indicative of the couple’s friendship with Lev Ivanovich.

Petipa’s next revivals were Trilby and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with Nikitina respectively dancing the title role and The Fairy of White Air. Petipa created Trilby for Moscow in 1870 and the ballet had arrived a year later in St Petersburg. It was loosely based on the novella Trilby, ou le Lutin d’Argail by Charles Nodier, a celebrated horror and fantasy writer. The imp Trilby, a travesty role, had been created on the student Lydia Geiten, later a celebrated Moscow Ballerina (in St Petersburg the role was first taken by Alexandra Simskaya). In Act I, Trilby teases the dim-witted brother of the heroine Bettli, Tobi, by quickly appearing and disappearing everywhere and nowhere around the room. Nikitina’s casting evidenced her fast-moving abilities. To facilitate these, she wore a costume that reminded Skalkovsky of a trapeze artist. Nicolai Soliannikov, a character dancer whose employment extended beyond WWII, was 10 when he saw Trilby, but remembered the scene’s details and speed; a cartoon avant-la-lettre.

1883 ended with the premiere of Petipa’s full-length work The Statue of Cyprus (Pygmalion). The grand, mythological ballet concerned the artist Pygmalion and his beautiful statue Galatea, granted life by Venus. The ballet, with both music and scenario by the Prince Ivan Trubetskoi, boasted a Grand Tableau Fantastique that assembled all the divine inhabitants of Mount Olympus. Nikitina was the Goddess Diana, leading four girls in the Pas des Chasseresses. ‘… Miss Nikitina was [...] excellent and danced her classical variation with total elegance ...’ (Novoe Vremya).

In 1884 Vazem retired, and Petipa saw a window for Nikitina with his revival of Coppelia. Swanilda brought Nikitina success and ballerina status (Natalia Roslavleva).

Khudekov: ‘… Then, especially for her, Saint-Léon’s Coppelia was staged, embellished with fresh, interpolated dances by Petipa. The role of Coppelia [sic] very much suited Nikitina’s talent. Her likeable gift was much evident there. Clearly expressed were the simplicity and childlike naïveté in the dances of the animated dolls. Graceful by nature, she developed her technique with stubborn labour and energetically exercising in class. But there was no breadth of flight; all her variations were fine, miniature, but owed their success to the artist’s attractive exterior ...’ On Act III: ‘… Miss Nikitina more than just dances [...] warranted the approval of all the savants for the cleanness, softness and elegance of her performance …’ (Novoe Vremya).

The young Alexandre Benois recollected how the ‘frail, slender and pretty Nikitina’ enchanted him, and then somewhat ambiguously attributes that to Delibes’s music rather than her dancing: ‘... weak in the leg, as with her slightly anaemic gracefulness ...’ A next assignment was a pas de deux in The Wilful Wife, Petipa’s reworking of the Romantic ballet Le Diable à Quatre.

1886 was an important year for the Imperial Ballet, because the company transferred from the Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre to the Mariinsky - right across the street. The inaugural piece was the ballet-féerie The Magic Pills, a huge enterprise. It boasted many parts, of which Fiery Love was created by Nikitina. As if this was not enough, another creation was presented a mere week later: l’Ordre du Roi. The court dance-filled work was a benefit performance for ‘the Divine Virginia’ Zucchi. Zucchi’s fame had preceded her to St Petersburg, where she first danced in 1885, in the Sans Souci Theatre. Soon after, Zucchi found herself officially sampled by the court, during the summer season at Krasnoe Selo with a pas de deux from The Voyage to the Moon. Her acclaim was rapturous. Nikitina spoke out in favour of hiring Zucchi for the company (Nadine Meisner). This should have been in compliance with Skalkovsky, who championed the diva, yet courageous because of a fierce opposition that included director Ivan Vsevolozhsky - and Petipa. To them, Zucchi was, artistically, too much of a free spirit for the company. They were overruled by the Tsar, who saw to it that she be invited to the regular season. La Zucchi continued her victory march from there.

Nikitina and Zucchi became friends, and in l’Ordre du Roi they shared the role of Pepita. It was the first of many times Nikitina would be second cast to an Italian ballerina. While Zucchi set a trend for Italian guests in St Petersburg, Nikitina herself made guest appearances, inter alia, in Berlin. She debuted on 5 April in the Opera Unter den Linden, dancing the pas de deux from Don Quixote, partnered by the German dancer Max Glaseman. After that came the ballet Wilhelmina, with Nikitina as Nuriada, a part originated by Antonietta Dell’ Era. The Royal Court Dancer was Berlin’s audience favourite (six years on, that same Dell’ Era would precede Nikitina as the first Sugar Plum Fairy). The Kaiser, Wilhelm I, attended Nikitina’s debut, the first Russian dancer touring Berlin in 15 years. Plescheyev wrote that Wilhelmina’s composer created the Nikitina Polka in her honour. The German newspapers spoke of Nikitina’s triumph, and were interested in everything about her, including her wardrobe. The Prussians bedecked her carriage with roses and lilies.

The following year saw a fresh, unpretentious ballet: Enchanted Forest, choreographed by Ivanov to music by Riccardo Drigo. It was created for the Theatre School, but a mere weeks later arranged for the company. Nikitina worked with her former teacher on the role of Ilka, who gets lost in the woods, faints, is wooed by the Genie of the Forest, faints again, and is then retrieved by her fiancé Iosi. An effective Czardas followed. Enchanted Forest, being the perfect vehicle for double and triple bills, held repertoire. One critic found Nikitina to be lacking in aplomb (Sanktpeterburgskie Vedomosti).

In 1888, Nikitina became yet another Pepita, in Ivanov’s The Beauty of Seville. It was a low-profile ballet for the Krasnoe Selo summer season, traditionally overseen by Ivanov. The Petersburg Gazette: ‘... Miss Nikitina and Mr [Pavel] Gerdt performed the final Spanish Dance, [the] Sevilliana, with the ardent passion and brio with which these public favourites are so generously endowed ...’ Another critic complained Nikitina ‘did everything on demi-pointe.’ Supposedly it was choreographed that way, but for all we know, Krasnoe’s relative freedom may have prompted Nikitina to wear soft pointe shoes instead of low-heeled ones, which then deluded this critic. More seriously, he found that her work ‘as ever, lacked sufficient finish.’ The Beauty of Seville returned the following summer, when Nikitina was (re-)acclaimed.

In 1889, the wedding of the Grand Duke Pavel Alexandrovich to his cousin Alexandra of Greece took place. To accompany the event, Petipa created Les Caprices du Papillon, an ‘insect ballet’ to the music of Nicolai Krotkov. It premiered in Peterhof’s romantic open-air theatre. Nikitina danced the leading role, The Butterfly. Aside from choreographic notations, an adagio for violin survives on 78s. It was clearly designed to exploit the talents of 1st violinist Leopold Auer, sounding like a tribute to Henryk Wieniawski (the Polish Wieniawski was Auer’s teacher). Caprices was taken into the repertoire.

1889 was also the year of Petipa’s grand ballet The Talisman, with Nikitina as second cast to the Italian ballerina Elena Cornalba for the role of Ella, the Heavenly Daughter who is tested against earthly love. Nikitina matched Cornalba and outshone her in grace and expressiveness (Roslavleva).

Speaking of grace, there is a lovely anecdote on how Nikitina’s kindness extended towards her colleagues, and it comes to us through Nicolai Legat. In his memoirs, he related partnering Nikitina as a young dancer in Le Roi Candaule. Nikitina impersonated the Goddess Diana in Les Amours de Diane, a part of the Act IV divertissement (her second Diana, after The Statue of Cyprus). Legat portrayed Endymion and Georgy Kyaksht the Satyr. Legat had adopted a sitting posture, waiting for Nikitina to throw herself into his arms. A technical morceau hard enough as it is, but Legat blundered when he extended the wrong leg, causing a loss of balance when she landed. It resulted in a tumble. Nikitina stood up and encouraged a confused Legat: “... No matter, my dear, let’s go on ...” As Doug Fullington’s reconstruction of the adagio does not show it, the episode pertains to the now lost coda. Legat cried and apologised in the wings, but Nikitina took his head in her hands and kissed him. This ‘touching kindness left an indelible impression’ on Legat. He remembered her ‘not only as a wonderful dancer, but also a wonderful woman.’ Nikitina had been the first ballerina Legat partnered, when replacing Cecchètti in l’Ordre du Roi, soon after joining the company (Kschessinskaya).

Later Career

Nikitina’s most celebrated roles arrived in the 1890s. The part that rocketed her to long-lasting fame was, of course, Princess Florine in Sleeping Beauty (3 Jan 1890). The single comprehensive collaboration of Petipa and Tchaikovsky became the imperial Mariinsky’s most-performed ballet. Nikitina danced a princess who is being taught to fly by The Bluebird: Enrico Cecchètti, a particularly airborne creature. Petipa purposely understated Nikitina’s own jumping ability here, as to accentuate the difference between bird and human. Moreover, as the piece brought a Russo-French and Italian-trained dancer together, it playfully combined and compared the two relevant styles of the day. One of the many favourable reviews: ‘… Miss Nikitina danced her pas de deux with Mr Cecchètti superbly, and was received by the public as it always receives its graceful favourite …’ (Novoe Vremya).

During the summer, Nikitina danced in the Krasnoe Selo season, where Cecchètti choreographed a pas de deux for himself and his Florine; an indication that their artistic partnership pleased him.

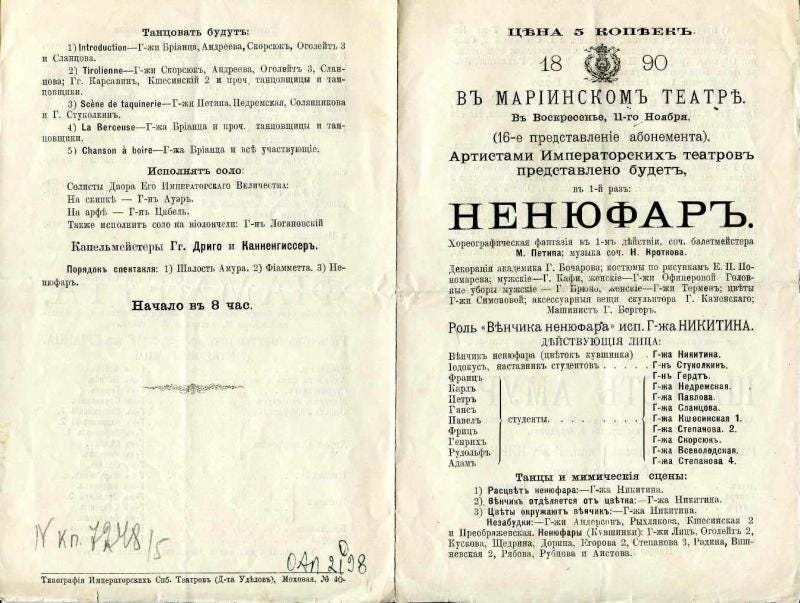

The end of 1890 brought the title role in the one-act Nenuphar - The Water lily. After Les Caprices du Papillon, Nenuphar was Nikitina’s second ballet to a Krotkov composition. The Nenuphar was a supernatural character, which Nikitina seemed to specialise in by that time (interestingly, associate records of the 1880s list her as demi-character artist, but the 1890s changed that). Nenuphar’s mortal suitor, Franz, was danced by Pavel Gerdt, backed by eight corps de ballet girls en travestie, all impersonating students. Unlike works such as The Daughter of Snows, The Hump-backed Horse and Sleeping Beauty, the concept appears to have been free of political, social or cultural allusions. Although Imperial Russia bordered on countries with opiate and hashish-using peoples, substances like cocaine and opium were neither a party drug of name nor a big lower-class problem. If Nenuphar would be on a Western playbill today, its selling point would be anti-drug abuse (think a web page film with needles and syringes floating about, guaranteed to slow down your computer), as the story’s students sample hallucinogenic flowers and pass out. The Nenuphar is no less dangerous than the other blooms. She does warn Franz against herself, but to no avail; he drowns in her smothering embrace.

Andrew Foster wrote about the 1916 restaging how ‘... Karsavina appeared in the form of a mermaid, a perverse and bewitching rusalka with an insatiable craving for blood and passion ...’ So, there was more to Nikitina’s stage persona, who must have revelled in portraying a baddy for once.

Nikitina then danced in Ivanov’s 1890 summer ballet Cupid’s Prank, as Oreada. Like Sylvia, a nymph better known to ballet audiences, Oreada was a favourite of the Goddess Diana (Oreads were a group of mountain nymphs). Ivanov obviously loved working with Nikitina, helping his fellow-Russian friend and one-time pupil where he could. Cupid’s Prank was another smaller piece that made the Mariinsky stage, if not for long.

Petipa, with his love for the Romantic ballet that had marked his formative years, revived two hallmark pieces for Nikitina: La Sylphide and The Naiad and the Fisherman (Nikitina had danced the 1st act in 1884). Both the Schneitzhoeffer and Pugni scores offered a plethora of catchy allegro music, ideal for Nikitina. Nicolai Bezobrazov wrote ‘... none of the foreign stages […] could boast of a better sylph ...’ and he went on to acclaim the adagio with Nikitina’s sylphide flitting between Pavel Gerdt’s James and Maria Anderson’s Effie. La Sylphide was not presented as a full-evening work; much like Bournonville’s version was not throughout the 20th century, or the early Russian productions. It was initially paired with an opera, the ‘lyrical etude’ The Poet, with music, incidentally, by Krotkov. Alas, these ballets were marginally programmed: La Sylphide was given five times during 1891/92, and in 1892/93 just once, while The Naiad and Fisherman got a mere two performances.2 It seems that Petipa had to wrench these shows from Vsevolozhsky’s hands.

Meanwhile, Nikitina’s social life did not stop. She moved in circles befitting her status as ballerina of the Imperial Ballet and befriended many colleagues. Among them were mezzo-soprano Maria Slavina, the celebrated singer who created Olga in Evgeny Onegin and The Countess in Pique Dame for Tchaikovsky, and the dancer Maria Peters Dandeville, at the time married to the critic Valerian Svetlov. A letter from this period to Skalkovsky reveals a dry sense of humour: ‘... Tomorrow I will have lunch with Frolov and Virginia [Zucchi], just the three of us. If they get drunk, I don’t know what to do. Don’t forget to put food into my present, I mean the canary ...’ (Ryleeva). Alexander Frolov, the manager of the Imperial Theatre School, adored Zucchi. The ballerina, who continued to tour St Petersburg after her Mariinsky stint (ending in 1888), was not exactly averse to a drink: She carried a flasket around which she nervously guarded, but Skalkovsky found out that ‘mama’s special, nerve-calming elixir’ was … gin.

Nikitina’s last role is a character that would become firmly rooted in Anglo-Saxon culture: The Sugar Plum Fairy. The Nutcracker was ‘born’ in the last month of 1892. Nikitina did not dance the premiere, but took the 4th performance (13 Dec), and then alternated with the role’s creator, Antonietta Dell’ Era. ‘... Miss Nikitina produces a more suitable impression [than Dell’ Era]. [...] in her slender, graceful figure, in her ethereal dances, The Sugar Plum Fairy is realised incomparably more successfully ...’ (Novosti i Birzhevaya Gazeta, 15 Dec 1892)

1892/93 proved to be Nikitina’s last season. She officially retired on 1 October 1893, after having been denied the opportunity to create Cinderella (Roslavleva). The fairy tale was in talks as early as the previous December, but it appears that Legnani was designated for it only months later, in July 1893 - half a year before the premiere. Did Nikitina see a window, prior to the time Legnani’s name started to circulate? But she had always been passed over by the Italians for the big premieres so far, so why would it be different for Cinderella? According to Plescheyev and Alexander Shiryaev, Carlotta Brianza did not serve out her contract due to her unacclaimed performance in Le Roi Candaule (16 Feb 1892). Skalkovsky, of course, sneered that Nikitina’s excellent Diana prompted her to go. A year later, Dell’ Era returned to Berlin (too) soon. Even if her departure was agreed upon, the directorate, needing their ballerinas to finish the season, cannot have been pleased. So, did these actions cause Nikitina to expect more opportunities, or even lend her the courage to go Oliver Twist and ‘ask for more?’ Think here of her boldness that led to the friendship with Skalkovsky, who undoubtedly egged her on for Cinderella. Taking this further, did Nikitina now push for big premieres (egged on by that same Konstantin Apollonovich)?

But Nikitina’s resentment plausibly built up over a longer period. Let’s look at the casting dynamics that marked 1892/93. Nikitina’s sensibilities were given a wire brush treatment by means of the ballerina roles of Kalkabrino, Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker. They are discussed in relation to her retirement wish as follows:

Nikitina and Kalkabrino

Firstly, there is the double role Marietta/Draginiatza from Kalkabrino, the lost ballet about a smuggler who gets his comeuppance by being dragged to hell. In November, Kalkabrino returned for its 3rd season. It was a meagre run of just two performances, yet these would have been ideal ‘crumbs’ for Nikitina (or, for that matter, Gorshenkova), like other ballets left vacated by their Italian originators - in Kalkabrino’s case Carlotta Brianza. Did Nikitina anticipate being cast here? She had every right. However, it was not Nikitina’s name that appeared on the cast list, but a rather unexpected one: Matilda Kschessinskaya’s. Petipa’s more off-than-on presence during this period could have been detrimental for Nikitina in this respect.

It is worth zooming in on Matilda Felixovna here. As a child she had been treated kindly and encouraged by Nikitina, and this continued as a fresh company member (they enjoyed lunch together on at least one occasion). Now a second soloist, Kschessinsky’s youngest daughter landed small solo parts, while gaining experience with principal role snippets at Krasnoe Selo. There she sampled an excerpt from Kalkabrino’s Marietta. Nikitina should have noticed Kschessinskaya’s design on the double role then, but may have been surprised at the reward it reaped: when 1891/92 started, Matilda Felixovna rehearsed Kalkabrino extensively with Cecchètti. As Marietta/Draginiatza was created for Brianza, Petipa can’t but have let his Italian School reservations go, aiming to show the ballerina to her best advantage - ergo, let his steps be influenced by her background. This means that Cecchètti was particularly suitable to coach it. Not only that, Cecchètti simply was the main ballet master around as 1892/93 commenced, for Ivanov was ill, and the exhausted Petipa was at his daughter Evgenia’s deathbed (he somehow managed to prepare Nikitina for Naiad). Without implying that Kschessinskaya was aware of the exact circumstances, she must have smelled an opportunity. But did she actually go to Petipa for Kalkabrino? Did she seek him out before the summer, cornering him in the school, making him nervously light up with a ‘fine, have it your way?’ In her memoirs, Kschessinskaya recalled how she, earlier on, had asked the 1st Ballet Master for Esmeralda. She was turned down for lacking life experience and heartache. As her pride must have been hurt, did she bypass Petipa altogether for Kalkabrino and go higher up, to Vsevolozhsky?

Whoever green-lighted it, that person undoubtedly had Kschessinskaya’s Romanov-ties in mind, with her strong technique as alibi. At the time, Kschessinskaya was set up by The Heir as his mistress and lived with her sister Julia - a chaperoning arrangement her father had insisted upon. Ironically, the Kschessinsky sisters rented the house that once functioned as the love nest of a certain Grand Duke: Konstantin Nicolaevich, Nikitina’s own royal connection. The question is raised: could he have done something for Nikitina? The answer is an unequivocal no. The Grand Duke had died in the winter, and long before that, his political death and then infirmity had let that source dry up - should Nikitina have stooped to ask for his help in the first place.

Kschessinskaya debuted on the 1st of November 1892 as Marietta/Draginiatza. She was thunderously received by audiences and critics alike. ‘Little K’ was put on the map. ‘… She gave a highly talented interpretation, which bore the marks of hard work and stubborn determination ...’ (Plescheyev). Cecchètti, after performing alongside his protégée, had his face showered with her grateful kisses during the curtain calls.

Can one argue that Draginiatza - in particular - was better suited to Kschessinskaya than either Nikitina or Gorshenkova? No. Insofar as typecasting played a part, Nikitina had the ‘blood-thirsty’ Nenuphar to her credit (and Gorshenkova was Nisia and the creator of Gamzatti). Neither did Nikitina lack the virtuoso abilities the double role required. Plescheyev commented: ‘... the boldest of Italians [receiving fabulous pay for a technical virtuosity equally well mastered by Nikitina] could be envious ...’ Think now of the ‘stubborn determination’ Plescheyev ascribed to Kschessinskaya. But Cecchètti appreciated Nikitina, his Florine, too. Did he try to get her in before Kschessinskaya came along? If so, he was plainly un-obliged. Politics reigned, that much is clear.

Nikitina, Aurora and The Sugar Plum Fairy

On 3 January 1893, Ivanov had his benefit. Since Dell’ Era danced Aurora (in Act I of Sleeping Beauty) on the festive evening, who would be a better choice for the Sugar Plum Fairy than its second cast - Nikitina? But the role passed to that same Kschessinskaya. Although this was necessitated by Nikitina being ill, she must have lied in bed seething nevertheless. If she had not yet figured it out with Kalkabrino, by then she knew for sure Kschessinskaya was a force to be reckoned with. And indeed, two weeks on, at 20, ‘little K’ managed to procure Aurora, the second role discussed in this context. Kschessinskaya debuted as the sleeping princess on 17 January. Again, she had the technique and quite possibly the artistry to dance Aurora, but inheriting it at that point of her career could hardly have occurred without a ‘royal network.’ Kschessinskaya’s modus operandi was not eschewed in Bezobrazov’s review: ‘... in ballet, fortune favours the bold, thanks to which, and also to her gift, Mlle Kschessinskaya mastered Sleeping Beauty ...’

Did Nikitina ask for Aurora? If she (had) voiced her designs on Cinderella, asking for a promotion within Sleeping Beauty was easier; Aurora was a coveted role but not a new one. Letting Nikitina, as ‘in-house ballerina,’ inherit Aurora from Brianza and Dell’ Era, was something the directorate could have endorsed. Comparably, Maria Gorshenkova had inherited Le Roi Candaule from Brianza.

Thirdly, there is The Sugar Plum Fairy. Because Dell’ Era left, Nikitina was the role’s supposed heiress, leaving Kschessinskaya with her one-off (Ivanov’s benefit). But nay. Nikitina did five more Sugar Plums, not all the season’s remaining shows, dancing her last on 11 April 1893. Following, she either became indisposed, refused the upcoming Sugar Plums - or Kschessinskaya managed to secure some more for herself. She danced the role again on 25 April and 6 May and was scheduled to do 1 April too, but cancelled. Anna Johanson substituted, which indicates that Nikitina declined to replace Kschessinskaya.

If this theory holds, with missing out on Marietta/Draginiatza and Aurora, Nikitina was not only deprived of adding to her hand-me-down roles (such as La Vestale and The Talisman), but with Kschessinskaya indulging in Sugar Plums, her own parts were now encroached on as well. She was being besieged from within by a dancer she outranked yet acquired leading roles overnight. Both Nikitina and Kschessinskaya were still on leave when The Nutcracker opened the following season (5 Sep). Anna Johanson took over again, being busy on opening night with both The Sugar Plum Fairy and Lise in The Magic Flute. In this light, it is credible that the Cinderella affair was merely the last straw for Nikitina - one can only take so many rebuffs.

Stage Farewell

There were no fewer than two Italian ballerinas announced for 1893/94, and the press knew about it since early May (Novoe Vremya). Of course, there would be Pierina Legnani, but Palmira Pollini, who preceded her in the autumn, was in effect engaged to fill Gorshenkova’s gap (she had retired in the spring). Pollini danced Nisia and Paquita, Gorshenkova’s other big role. Because Pollini also did Nikitina’s parts, La Vestale and Naiad, the question is: was she asked to do this additionally on short notice - meaning Nikitina had snapped and ran out throwing plates?

But Nikitina’s time of service totals a neat 20 years almost to the day, and so her retirement was no impulsive decision, but a well-considered move – albeit made after her ballets Naiad and Vestale had been announced.

Nikitina’s dissatisfaction took shape with her refusal of two extra seasons and a farewell benefit, a high-profile performance to which she was entitled. Nikitina was playing a trump card here. Yes, it would mean foregoing extra cash and luxurious gifts, but as a well-off woman, she did not need them. It does subdue Khudekov’s accusation of her being spoilt and receptive to presents. More importantly, it would - and did - attract the attention she was after. As never before, the press would write about her plight: a neglected Russian talent. This way, her message was stronger than when expressed from behind sizeable flower arrangements and silver wreaths. Did Nikitina’s friends in the fashionable circles that vehemently promoted national art influence her decision to leave the theatre? Did she agree to be their flack? If so, the outcome would not have changed.

Certain is that Nikitina’s friendship with Zucchi proves she had no issues with the Italian ballerinas personally. She had issued with not getting what she, as a top-ranking dancer, deserved - regardless of the reason. The day Nikitina’s career ended, 1 October, was also the date of Kschessinskaya’s promotion to first soloist.

When the century neared its end, Skalkovsky produced a retrospective collection of essays, In the Theatre World, wherein he addressed the problem home-trained ballerinas like Nikitina experienced. The critic opined that, during the 1880s, their failure to draw crowds to the big ballets was caused by over-familiarity from shorter ballets and solo roles. Skalkovsky compared the ballet with (the soon-abolished Italian) opera: bringing in international guests guaranteed box office throngs - interestingly, today’s modus operandi of Western opera companies. But back in the day, the directorate - by extension the country’s ruling body - should have balanced the rock star-proportioned guest climate by promoting Russian ballerinas in a parallel plan; shaping events rather than reacting to them.

Post-retirement

Nikitina, never forewent socialising with her friends and former colleagues. Iosif Kschessinsky reminisced visiting her in the spacious apartment on Gagarinsky. He often caught her alone, since Bazilevsky spent most of his time at the Kamenny Island palace, adding he was so enchanted by her eyes, full of charm (…). Bazilevsky died in 1895. A year on, Nikitina was among the guests in the famous restaurant Cubat to celebrate her peer Maria Petipa’s benefit. In 1901, Skalkovsky celebrated 40 years of literary activities. Nikitina was one of the speakers. Soon after his jubilee, Skalkovsky relocated to Paris, and a little later his friendship with Nikitina became rocky. Nikitina’s last found letter to him is from December 1904, wherein she adopted a reproachful tone (Ryleeva). If this was indeed the ultimate letter of their correspondence, a cherished friendship that began with her being reproachful live (remember the meeting in the theatre), ended reproachful too - on paper. Skalkovsky passed away less than 1,5 year later. Nikitina herself died from cervical cancer in 1920. She was 63.

Postscript

We are back at Karsavina and Pavlova, child witnesses to Nikitina’s Sylphide in 1892. Six years after Nikitina’s retirement, in 1899, Pavlova, her ‘spiritual successor’ graduated. It has been mentioned that Nikitina had the technique to match ballerinas of a different fach; however, she lives on as a Romantic ballerina in ballet’s classical period, while the Romantic ballerina Pavlova arrived on the brink of the modern age. Of course, there were more differences. On photos, Nikitina’s body seems to contain energy, whereas Pavlova’s radiates it. While it is safe to assume Nikitina remained technically superior, Pavlova’s artistic range was broader. But Pavlova’s expressing herself from air spirit to bacchante, dramatic ballerina and back, happened because the theatre let it happen. Pavlova’s break-through roles, Nikiya (1902) and Giselle (1903), come off as an unintended redemption towards Nikitina. A correction by history. Incidentally, Varvara Alexandrovna herself was spotted in the audience for Pavlova’s debut as Giselle. Later that year, Pavlova continued her advance with Undine in The Naiad and Fisherman. Two of Nikitina’s roles Pavlova never danced that suited her talent were Ella/Niriti in The Talisman and ... La Sylphide. Although Pavlova did not become ‘La’ Sylphide, she did become ‘a’ Sylphide, in Fokine’s Chopiniana, as did that young audience member from 1892, Tamara Karsavina. La Sylphide. Les Sylphides. This points to a third legend who saw Nikitina as sylphide: Mikhail Fokine, creator of Chopiniana/Les Sylphides.

So, while Nikitina herself fringes mainstream ballet history, it is overlooked that she was the single vessel through which Taglioni’s images and culture came alive for the young artists Pavlova, Karsavina and Fokine.3 Through them, the Romantic legacy was preserved and spread,4 and it was the strength of their artistry that enabled the sylph float through a time and age that could have burnt her wings far too easily.

© Peter Koppers

Notes

1) Marie Taglioni appeared in St Petersburg from 1837 to 1842, dancing a variety of ballets.

2) 1893/94 saw another two performances of Naiad, but Nikitina had left by then, and Undine went to Anna Johanson.

3) Not counting the sylphide’s thematised image in other ballets, like Camargo (1901), seen and danced in by Pavlova, Fokine and Karsavina.

4) Bournonville’s La Sylphide played a part here too, but the ballet remained somewhat isolated during the first half of the 20th century. The sylphide as ‘popular image’ should be ascribed to Pavlova, Fokine and Diaghilev.

Sources & Bibliography

Sergey Belenky

Doug Fullington

Amy Growcott

Sergey Konaev

A Century of Russian Ballet, Roland John Wiley

Anna Pavlova - Her Life and Art, Keith Money

Dancing in Petersburg, The Memoirs of Kschessinska, translated by Arnold Haskell

Diaries, Matilda Kschessinskaya

Era of the Russian Ballet, Natalia Roslavleva

Imperial Yearbooks

Jules Perrot, Ivor Guest

Marius Petipa, Meister des klassischen Balletts, Eberhard Rebling

Marius Petipa: The Emperor’s Ballet Master, Nadine Meisner

Materials on the History of the Russian Ballet, vol. II, Mikhail Borisoglebsky

Memoirs, Alexandre Benois

Memoirs, Iosif Kschessinsky

Nash Balet, Alexander Plescheyev

The Petersburg Ballet, Alexander Shiryaev

Soviet Studies Vol. 42, Mary Schaeffer Conroy

St Petersburg Library

Tamara Karsavina, Diaghilev’s Ballerina, Andrew R Foster

The Life and Ballets of Lev Ivanov, Roland John Wiley

The Russian National Library

The Story of the Russian School, Nicolai Legat

The Sergeyev Collection

Varvara Nikitina to her Circle of Friends, Maria Ryleeva

Photo Credits

A.A. Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum, Artchive, Bolshoi Archive, St Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music / Санкт-Петербургского государственного музея театрального и музыкального искусства, St Petersburg State Theatre Library / Санкт-Петербургская государственная театральная библиотека, Mariinsky Theatre Archive, Collection of Peter Koppers, Salvador Sasot Sellart